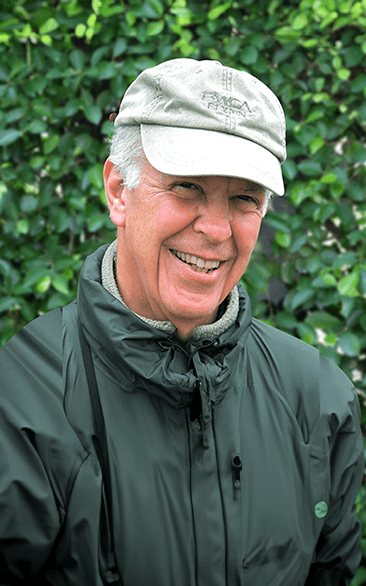

Kate Bowler: There are the ways that things are supposed to be. Meaningful, rosy, Hallmarky. And then there are the way things actually are. Disappointing. Frustrating. Rarely as meaningful as we would hope. Is blegh a word? And then there we are in the middle. My guest calls it the tragic gap, that space between all that we’re navigating as we try to be people of hope and action in a world that is not so cinematic. Or at least maybe not like the movies we want to watch. Maybe French movies. I’m Kate Bowler and this is Everything Happens. Today I’m speaking with Parker Palmer. Parker is a writer, teacher and activist. He’s the founder of the Center for Courage and Renewal and holds a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of California at Berkeley. He has written ten books that have sold over 2 million copies, including Let Your Life Speak and Healing the Heart of Democracy. And Parker, as of this conversation, is 85 years old, and you would never know it because he stays just as hopeful and engaged as ever. But he wasn’t always this way. As you’ll hear, he’s gone through seasons of deep clinical depression, and he has hard won wisdom to share with us on how to survive, how to regain a sense of agency, how to remain hopeful despite it all. Despite the politics that try to tear us in two. Despite the despair that is so tempting, despite the fear mongering and doomscrolling and othering that we see all around us. So on a day like today, when we all might be thinking about the state of our nation or the state of our world, or the realities at stake for our family and friends, or maybe be tempted just to put your head in the sand and try to make it through Thanksgiving, might we pull up close and listen to what Parker has to teach us about how to keep our hearts soft and remain hopeful still? So listen up. It sounds very bossy, but you really are going to love this one. I am an annoying superfan. So I came all the way to glorious Madison, Wisconsin to talk to him. Oh my gosh. It feels so good to sit down and see your lovely face.

Parker Palmer: Thank you, Kate. It’s so good to be with you.

Kate: I wondered if we could start with a season that you had that was a dark night of the soul of wondering what is going to happen to our communities. That feeling of afraid, sad individualism you saw everywhere, because I’m kind of wondering if we’re in a moment like that right now.

Parker: Well, how much time do you have?

Kate: I got at least an hour.

Parker: Part of my life’s story is three deep descents into clinical depression, two in my 40s, one in my 60s. In all three of those instances, the mix that went into the making of that dark night of the soul was partly personal internal questions, issues, wrestling matches with things like vocation and aging and relationships. But it also had a worldly context. It had a political context, and I could point to those various areas of my life and people would quickly understand, oh well, if it wasn’t the current threat to democracy in the United States, it was all the threats that came with the Vietnam War or all the threats that came in the middle of economic global collapse or all the threats that came with impending, the impending destruction of our environment. I mean, these things bear in on us, don’t they? And there’s no way to live a life that’s encapsulated and protected from all of those destructive dynamics. Depression isn’t just about feeling lost in the dark. It’s the sense that you’ve become the dark. You know, when you’re lost in the dark, you can negotiate the darkness, right? If I’m lost in a dark room I can feel around. Maybe there’s a door here. Maybe there’s a window shade over here. Maybe there’s a light switch somewhere. I can find some way to kind of deal with the situation I’m in and keep a little hope alive. Because maybe there will be a little light that I can bring into the room. If you’re not lost in the dark, but you’ve become the dark, there is no negotiating it. You’re it. It’s you. That’s all she wrote. And I’ve been there a few times. It’s a devastating place to be.

Kate: It really makes me think of experiences in my own life where I’ve seen people be genuinely overwhelmed by despair and that it can swallow up days and weeks and years. And then also moments where some people had tremendous sadness, like I had a friend whose husband died, and then all the sadness had all kinds of meaning in it. But then it after his death, it sort of morphed into something else. And she became incredibly despairing about the environment. And it took me a while to be like, why are you? I mean, we’re all upset about single use plastics, but why are you so upset about single use plastics? I think it was part of this exchange of agency, like just trying to figure out if I can’t act in this one way and that I want so desperately, now I feel acted upon by these bigger forces. I imagine we’re all just trying to find it, right? Like, how do we set the dial for what we are able to do? And it sounds like both personal, I love your framing of like, both personal reasons and geopolitical reasons and kind of like adjust the volume on that.

Parker: Right? Because it does, some of these feelings do route, don’t they? In this sense, we carry around in quote normal life, that I’m in charge of what happens to my life. And I am probably partly in charge of what happens to your life, you know, as we sit here together. And it’s a lie. I’m not in charge of any of that. I can contribute to a dynamic in my own life, or between you and me. I can contribute in a life giving way or I can contribute in a distilling way. Those are choices I do have to make. But in the kind of depression we’re talking about, as you just suggested, your sense of agency is gone. And so one has to find some way, especially hard when you’re just utterly down and out, to reclaim a little sense of agency. I was talking with this therapist who said, what I want you to do in the midst of this despair you have about being nothing and nobody and of no use, a worm, I want you to start keeping a journal. And I just, you know, drew whatever energy I could and did the fair imitation of a depressed blow up which isn’t a real blow up because you just don’t have the energy for a real blow up. But I said, are you out of your mind? I can’t write a sentence. I can’t read a page. I get lost in the very act of trying to articulate a thought or absorb it sort from the outside. He said, well, I’m not talking about a lengthy discursive journal. I’m talking about a journal of tiny achievements. And I said, what does that mean? And he said, well, for example, you told me that you were finally able to get up at 10:30 this morning, having spent most of the night and morning just in a darkened bedroom hiding under the covers. He says, write that down in the journal. You also you also told me that today you were able to get out on your bike, which is your preferred mode of exercise, because you don’t have to talk to anybody when you’re on a bike. And in this state, you’re incapable of even a simple conversation with a neighbor. You were able to ride your bike for ten minutes. Write it down. Tomorrow, start a new page with a new date. What you’re going to find, if you are faithful to this simple, this journal of tiny achievements, you’re going to find that you’re getting up a little earlier from time to time. You’re going to find that you’re riding your bike a little longer from time to time. The day’s going to come when things are going to start feeling a little more normal from time to time. The pattern of depression is sawtooth. It’s sometimes better, sometimes worse, day in and day out. Now, I was a guy for whom an achievement was writing a new book, selling 100,000 copies, getting great reviews, being invited to give talks and workshops all over the country. That’s how I spent 40 plus years of my life. These didn’t seem like achievements at all. But I today, to this day, in good mental health and in times when things are a little dark, I have recalibrated my sense of what an achievement is, and I embrace myself over much smaller achievements. And at age 85, when I probably don’t have another book in me and I don’t have a lot of post-COVID travel in me, this is probably as important as it was to honor my tiny achievements as it was when I was in deep depression. It’s a tool. And for me, it worked.

Kate: I’m always obsessed with these ways of describing the space between everything is possible and nothing is possible because I spent so much time studying everything-is-possible-ism religious cultures, which then morphed into like wellness, self-help world. And then I have so much sad, intimate awareness of the nothing-is-possible-ism having grown up in a home with a lot of clinical depression. But this space that you’re describing is so exciting to me because there’s so few ways to be honest and concrete and not absurd about it.

Parker: You’re reminding me, Kate, of a poem that I wrote. Poetry has been a great gift in my life, reading it first and then writing some over the years. And in the middle of one of my depressions, I took a retreat out in the country because there was a, the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Loretto was in Narinx, Kentucky, and there was a sister there whom I had come to know, a wonderful woman named Elaine Prevallet, and I wanted to just hang around for a week and get spiritual guidance from this very grounded person who would never say, you know, cheer up, things are going to get worse. To which my answer always is, so I cheered up and sure enough, things got worse.

Kate: I’ve actually never heard anyone say that said, cheer up, things are going to get worse worse. That’s so funny.

Parker: People’s slip of the tongue. You know, it’s very telling.

Kate: Please send that to me in a voice memo someday.

Parker: I shall, I shall. So there I am out in the country and I’m walking down a country road one day. No traffic. Plowed field over here. Plowed field over here. Sometime in the late spring. And I have enough of a farm background from my father’s family in Iowa to know that that field has been harrowed. And so that word was living with me harrowed.

Kate: And what is harrowing mean for people who are not as farmy as we are.

Parker: Harrowing is when you take a tractor and a plow with brown blades or sometimes just fork blades and you drag it across the field to loosen up the soil, to move things around prior to finer plowing and planting. So it’s, a harrowed field is a jumbled field. And it’s the first step in a process. So this poem came to mind, I worked on it slowly over the next few days and it’s lived with me forever. I have it memorized. I can usually come up with it. Let’s see how it goes. It’s called Harrowing. The plow has savaged the sweet field. Misshapen clods of earth kicked up. Rocks and twisted roots exposed to view last year’s growth demolished by the blade. I have plowed my life this way. Torn up a whole history, until my face is ravaged, furrowed. Scarred. Enough. The job is done. Whatever’s been uprooted, let it be seedbed for the growing that’s to come. I plowed to unearth last year’s reasons. The farmer plows to plant a greening season. That poem has mana in it for me, power, you know, elemental power. It told me what I needed to do with this harrowed face, this harrowed heart, this harrowed body, this harrowed field. And it was all about planting a seed if I ever had one. And then another one. And another one. To recover again that sense of agency, that tiny achievement and let it grow.

Kate: The part that really hit me was the undoing. I’m so worried about, like, like undoing last year’s reasons. Is that what you said?

Parker: The firmer I plowed to unearth last year’s reasons.

Kate: Because so much of the pain that we experience is that the stories that aren’t quite coming true.

Parker: Or like it’s my fault.

Kate: Yeah. Yeah. Like the people that should have loved us better, frankly. Things that should have happened. Things maybe we should have done. And it’s just, there’s so many things to undo, to like, to pull up, to have anything new happen.

Parker: Yeah I, you know, I sit here now, Kate, at age 85 and truly I can look back and understand the way in which everything belongs. I think that’s maybe a Richard Rohr phrase.

Kate: Sounds like Richard Rohr doesn’t it?

Parker: It does. Yeah. And, everything had a place, everything had a role, and I was at the time doing the best that I knew how under the circumstances. For me, it’s just that simple. If I can understand my life as I lived it on the terms with which I was living it at the time, there’s a lot of liberation in that, and I think forgiveness is about liberation. Liberating myself and liberating the other people in my life from whatever burdens I might want to put on them because I haven’t got my act together.

Kate: We’re going to be right back after a break to hear from our sponsors. Don’t go anywhere. In the same way that you were able to have compassion for yourself for like a personal depression and sort of a generalized sadness about where we’re going as a democracy, I wonder if we could give people some hope who just feel like pretty tired going into this political season. How are we supposed to grow away from our sad independence and into caring about other people when other people are so crazy? Or you can insert any word when other people make me feel misunderstood or when other people don’t seem to share any of the same values that I do? And we’re always at odds?

Parker: One thing I want to say quickly before I forget it is that so much of what you’ve described, I think, is people operating off the narrative offered by the mass media. And I’m not talking now about the mass media truth telling, the mass media lying, all those debates about fake news, blah, blah, blah, though there is plenty of fake news out there and there’s twisted news, there’s biased news, etc.. I’m just talking about the big picture that the news media online and in print deliver to us every day, and people absorb every day, which somehow then forms people’s sense of the reality in which they’re living. But wait, the reality in which you’re living is in your home and out the front door and down the street with neighbors and, you know, some voluntary associations you belong to and the interactions you have at Farmer’s Market and the conversations you have with people who are struggling with their own lives, which aren’t highly ideological, that they’re just about things like people dying and people suffering and people not getting the job they wanted or people getting the job they wanted or finding the apartment that they wanted, and, you know, finding a way to put food on the table. We need to recalibrate our sense of what’s the reality in which we’re living, number one, and I find that when I do that by walking out my front door, walking through the park, sitting in a playground, talking with parents and their kids, that things look better than they did in the Wisconsin State Journal or on The Daily Beast or the HuffPost, right? So that’s that’s one thing.

Kate: So if you want to feel less absurdist about the world, talk to more, reduce things to the scale of your actual life.

Parker: The second thing I would say, there’s a deep challenge here to the mythologies that I carry with me about how history unfolds and about what this country is all about. Ask any thoughtful Black brother or sister, you know if the United States today is in just a lot worse shape than it was 250 years ago or 200 years ago or 150 years ago or 100 years ago, and the answer you will get is no way. This is just the way the United States is. You know, we have always had this streak of cruelty that runs through our culture. Have we had streaks of brilliance and of generosity? Absolutely. But there’s always been this streak of cruelty, too. Our entire economy was founded on the obscene, evil enslavement of men, women and children whose families were destroyed generation after generation after generation. I spent some time right out of graduate school as a community organizer in Washington, D.C., you know, walked away from an academic appointment after I got my Ph.D. to try to respond to the racial crisis of the late 60s and early 70s. Community organizing in D.C. around issues of racial justice was my first introduction to serious engagement with Black activists and I have learned from them that there is not only the fierce urgency of now, which we are all called to. There is also the honoring of the ancestors. I mean, 14 generations of ancestors who used the tiny, tiny degrees of freedom they had to plant this seed and that seed. Sometimes in a religious context, sometimes in a secular context. And to keep planning and to keep planting and to and to grow this crop into changes in the way in the law of this land. And one thing I absolutely refuse to do as a human being, and this is where I think nice middle class Americans have to get just a little bit feisty and pissy, I refuse to succumb to the politics of divide and conquer. I refuse to listen to those noxious voices from on high who are telling me, look, distrust that person, distrust that person, hate that person. That person’s up to no good. That’s B.S. And it’s an ancient political strategy designed to disempower me from citizenship, because if I can no longer have a network of trust among those, at least among those people with whom I walk out the door and meet, I can’t be a citizen of this democracy. You can’t be a citizen of this democracy just by running a solo act called voting once every 2 or 4 years. You be a citizen of this democracy by engaging with others around shared concerns and the direction you want the country to take. Will you save the day? No. But no day has ever been saved by an individual act. And here’s the big, big frame. We live as humans, always have lived, always will live in what I call the tragic gap. And it’s tragic not just because it’s sad, but because it’s inevitable in the Greek sense, in the biblical sense, in the Shakespearean sense. Tragic isn’t just sad. It’s built into the nature of things.

Kate: We’re living inside of forces we cannot control.

Parker: We’re living inside of forces we cannot control. And yet our job is to keep putting one foot after the other in that tragic gap, attempting to achieve something better, something better, something better. So the gap between what is and what could and should be is huge. It will never close. But our job is to keep from slipping out into corrosive cynicism, which says, oh I see how the system works, I’m just going to game it, get what I can and let the devil take the hindmost. Or, on the other hand, flip out into irrelevant idealism, which is just trust God, everything will be fine. Or trust, I don’t know, some countercultural guru and everything will be fine. Both of those, those sound like radical opposite ways of coming to life, corrosive cynicism and irrelevant idealism, but they function exactly the same way. They take us out of the gap. They flip us out of the gap. Our job is to keep putting one’s foot after another and stepping forward in that tragic gap, doing what we can every day, recording it in our journal of tiny achievements and understanding that it counts. It matters because there is no social change in the history of humankind that has been accomplished in one fell swoop. Every one of them has been accomplished by a million million tiny steps over usually generations. And recovering our democracy is a generational job.

Kate: Wow.

Kate: We’re going to take a quick break to tell you about the sponsors of this show. We’ll be right back. If we think of ourselves as a very sad but also kind of broken in certain parts person, it can feel like, well, that’s not the person who is going to be able to help very much, do very much. We’re already consumed by all the things that have made our lives difficult or tragic in the first place. We are already too aware of the fact that we are living inside of like crosscurrents of things we can’t fix. Kids with intractable problems. Parents with intractable problems. Jobs with intractable problems. But you and I both agree that there’s something weird that happens to the broken hearted, is that there’s like, a kind of an inside-out-ness that happens that can make us maybe exactly the right people to live in unfinished times.

Parker: I think so. This level of engagement, either in politics or in personal and communal life seems to me to require the kind of opening that can comes through broken heartedness. Absolutely. So just as you said, I’ve thought a lot about the fact that there are two ways for the heart to break. It can shatter into shards and just lie useless on the floor, never to be put back together again. Or you can exercise your heart on a daily basis by taking in the little losses, the little deaths, you know, those things that are feel hard to absorb, the news that’s hard to absorb, take it and let it exercise that muscle the way a runner exercises muscles so they won’t snap under stress, and the heart has a chance then to become so supple that it will break open into largeness rather than apart in into shards. And, you know, the most trustworthy people in my life are people who have known broken heartedness, and those who have known it in depths. Those are the people I can go to and say, and tell it the way it is for me. And then, and in the process, experience healing. They don’t have answers for me anymore than I have answers for them. But we can have a conversation rooted in broken heartedness and honesty about that experience that goes somewhere humanly, right? And that makes me feel, and I think makes them feel, welcome to the human race. That’s to me, that’s the best words I can say to anybody, that, you know, whatever it is you’re you’re feeling, whatever it is you’re wrestling with, welcome to the human race. This comes with the package of being human.

Kate: Do you think this quality of, when you meet somebody and, you know they’ve really been through it and it opens up kind of an emotional generosity around life. Do you think that that’s something that more people age into? Or is it still like a secret club?

Parker: There’s a phrase in the scripture, I’m not enough of a Bible student to know exactly where it’s found, about Jesus, that he was a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief. And I’ve always felt, despite all the mythology around Jesus and all that I can’t trust about some of his current representatives on the face of the earth, there’s something deeply trustworthy about that description. And if a person were really living into that description, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief, that particular person would not be busily at work spreading around more sorrow and more grief in the midst of American democracy and a world scene that is drifting slowly back to the fascist hole of life. You just wouldn’t because you know something that would keep you from going there. So yeah, we can talk about trustworthy Christians as well as trustworthy members of the general population. Unfortunately, I see people aging toward bitterness and resentment and the closure of minds and hearts. You know, I wrote this little book about Grace, On the Brink of Everything: Grace, Gravity and Getting Old. My publisher wanted a softer title than getting old. I said, no, it’s about getting old, for goodness sake.

Kate: We’re lucky we all get to do it.

Parker: Exactly. Congratulations. But you know, in that book I said something like, old is just another word for nothing left to lose. And that’s how I feel. You know, I told a friend the other day who asked me, well, what about the next steps in your life, Parker? I said, look, I have nothing left to prove. If I do, I don’t have time to do it! So me, I’m enjoying life and I’m here, you know, for the ride. I want to continue to contribute my gifts. So it’s not all ride. It’s also work. But I want to do it with a sense that I don’t have anything left to protect or cling to or demand that the world not mess with, you know.

Kate: Living in hyper reality when we know too much and not enough at all times. And we all have a vague awareness about almost every topic, but typically not enough to do anything on a policy level about it. You’re a big advocate too, of shutting it down and living to scale, taking a break, not inundating yourself with so much information. Could you talk our lovely listeners into a rest, into just simmering down for a second?

Parker: I’m grateful to the Quaker tradition. I’ve been hanging around with Quakers since I was 35, I guess for 50 years, and I’ve learned a lot from them about the power, the value of silence, which I did not learn in my mainline Protestant upbringing.

Kate: I like talking. You like talking.

Parker: Yeah, right!

Kate: More of a talky club.

Parker: Yeah. And whenever the minister said in the church, I grew up in the Methodist church, now we’ll have a moment of silence. The organ broke into loud pouring for sixty seconds so that none of us could hear what we were thinking. Which was precisely the point.

Kate: Oh my gosh my son said something like that the other day. He goes, why do you keep, he said it so sweetly, but he was like, why do you keep bringing me to this place where they keep saying listen to God, but everyone’s talking.

Parker: Exactly, oh I like that a lot. Tell your son that’s so good. Exactly. So I learned a lot from the Quakers who don’t worship the silence. They worship in silence, and what they’re doing is listening. And Quakerism has its problems, just like every religious tradition or sect does. But I have seen wonderful things come out of that silence where people kind of touch a bedrock of truths. It emerges in vocal ministry, as Quakers call it. And community starts happening around those deeply held concerns. Because so often when we speak from that place of depth, we’re tapping into the aquifer that feeds all the wells. And it turns out that other people, as they tap in, are feeling that same thing or getting that same message. And then we’re poised to do something that’s real and could well make a difference in the world.

Kate: I sort of wanted to as we close in an awkward, I’m just going to read you to you for a moment your Habits of the Hard. Understand that we are all in this together. Develop an appreciation for the value of others. Cultivate the ability to hold tension in life giving ways. Generate a sense of personal voice and agency. Strengthen our capacity to create community. These beautiful little ways that we have to get rewoven into each other. It’s going to require a lot of like discipline and belief that other people are doing it, too. Because otherwise I think we will get swept away by the tides of the algorithmic overlords. And we won’t be able to see each other anymore.

Parker: You know, Kate, as you well know, when I wrote those words in Healing the Heart of Democracy, I set them in the context of what Alexis de Tocqueville said about American democracy, this great 19th century interpreter of the American experiment, as it very much was at the time. He came to this country from France in 1830 or so. I think it was. The country was very young. It was fresh and raw and a lot hadn’t been worked out. But he had, he wrote a two volume work called Democracy in America that a lot of scholars will say is still among the very best things ever written on this topic. He rootex all of this habits of the heart stuff in the voluntary associations to which Americans belong. And somewhat against his will because he was from France and he wasn’t real keen on Christianity, he realized, among those voluntary associations are the churches. So if this is going to happen, if these habits of the heart are going to be actively cultivated, we have to look to those local venues of life in which people live and move and have their being on a daily basis, not on that grand scale, but in the microcosm of our lives and trust the fact that there are millions upon millions of those microcosms. And do what we can to enrich the human scale life in the microcosms that we inhabit. So what are you doing with your kids along the lines of these habits of the heart? What are you doing with your neighbors along the lines of these habits of the heart, which are an interlocked set as you know, it’s not just five sort of data points. So what are you doing with the church you belong to, which may be in need of someone standing up in the pews and calling B.S.. You know, it could be in the workplace. There’s so many venues of common life that are left. Do we have to enrich them? Are we bowling alone these days? Yeah, we are. I get that. But I don’t like seeing that argument phrased as if it’s all done. It’s all over. One of my favorite quotes recently comes from a woman whose name I believe is Sherrilyn Ifill, who was the head of the Legal Defense Fund of NAACP. She stepped down after a long and honorable tenure in that role of trying to advance civil rights causes and doing a very good job at it. And as part of her farewell talk, she spoke a line that I hope always to remember. She said, I’ve read a lot of Black history in detail. I’ve read a lot of narratives of my people and how life has unfolded for them over the centuries. And never, ever at the end of one of those narratives have I seen the phrase or heard the phrase, and then we gave up. I’m not ever going to speak that phrase either about my own life, about my own engagement.

Kate: Parker. What a ridiculous joy to have this conversation with you. I’m open to you bossing me around for at least the next 5 to 10 years. Feel free any time.

Parker: Yeah, I don’t think so, Kate.

Kate: I’ve conscripted you.

Kate: One of the hallmarks of this gorgeous listening community that you are is that you are the people who know what to do with a broken heart. It is what stirs your empathy. It is what reminds you of our shared humanity. It is what propels you toward action. So just in case you’re ever tempted to let your broken heart harden you, might this conversation be a reminder that staying soft is your superpower. Here’s a blessing for keeping your heart soft when everything is broken. Blessed are you who see it all now. The beautiful, terrible truth that our world, our lives seem irreparably broken. And you can’t unsee it. The intractable problems. The person who wonders if any of this is worth it. All the loneliness and despair and fear. Blessed are you who glimpse reality and don’t turn away. This kind of seeing comes at a steep cost and it is a cost that you may not have paid intentionally. But here you are seeing things clearly. Blessed are you who have worked hard to keep your heart soft. You who live with courage, fixing what is in your reach. Praying about what is not. And loving still despite difference. Despite despair. Despite all the reasons to shut it down. May you experience deeper capacity and glimpses of hope as you continue to see the world as it is. Terrible, beautiful, fragile.

Kate: All right, darlings, we would love to hear from you. In seasons of deep depression, Parker started recording his tiny achievements. And I’d love to hear yours. How are you redefining achievement in this season of life? What is one tiny achievement you want to celebrate today? Write me a note on social media, I’m at @katecbowler. Or leave us a voicemail at (919) 322-8731. And before you go, if you could possibly leave us a review on Apple or Spotify, it really helps people find the show. And I promise it only takes a couple of seconds. And a big thank you to my team and our partners for the work that they put into this episode. Lilly Endowment, the Duke Endowment and Duke Divinity School support all of our projects. Today’s episode was made possible by our colleagues at the Duke Religion and Social Change Lab, an interdisciplinary team of researchers who help current and emerging faith leaders adapt to evolving times. In other words, they serve those who want to serve well. This podcast is full of all my very favorite people in a giant pile. A huge shout out to Jessica Ritchie Harriet Putman, Keith Weston, Baiz Hoen, Gwen Heginbotham, Brenda Thompson, Iris Greene, Hailie Durrett, Anne Herring, Hope Anderson, Kristen Balzer, Eli Azanio, and Katherine Smith. I would be absolutely nothing but crawling out of a hole of small productivity without you. I’m going to talk to you all next week, my loves And I got a chance to speak with Wilma Dirksen. I have wanted to talk to her for years. She shares so candidly about what it means to choose to forgive the unthinkable and live with what you cannot change. You will not want to miss it. Sign up at katebowler.com/newsletter so you won’t miss an episode. This is Everything Happens with me, Kate Bowler.

Leave a Reply