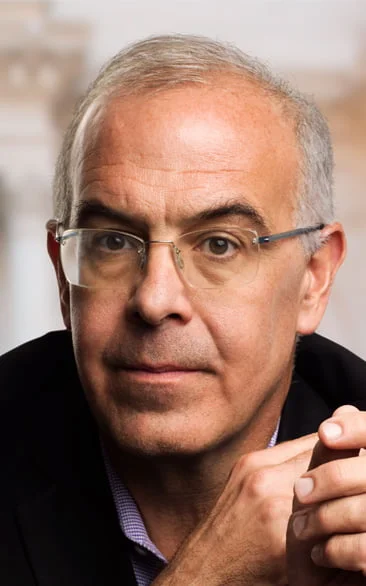

Kate Bowler: I’m Kate Bowler, and this is Everything Happens. We may think we understand people—where they’re coming from, why they act the way they act, what makes them tick. And I always assume I know why someone else is doing something. But what if we’re wrong? How do we get better at really knowing people? And might that skill help us combat the loneliness, the despair, the tears in our social fabric, our way of being together? Today. I’m speaking with David Brooks. David is an opinion columnist for The New York Times, where he writes about politics, culture, and social sciences. He is also the author of bestselling books like Bobos in Paradise. Oh, my gosh. I had that on my bookshelf as a teenager. He has also written The Road to Character, The Second Mountain, and his latest, How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen. And David is also my friend. He has been a clutch friend to me, and I feel so lucky to get to sit across from him and have this conversation about the importance of friendship. About why we crave intimacy and connection so much, and just how to get better at knowing the person in front of us. You’re going to love this conversation about, you know, conversation.

Kate: David, I love that we’re…well, I always love seeing you. And I also like that we’re having tea. Given that at the beginning of your book, you describe your upbringing as being not like the most emotionally…open. You had, like a…what was it? It was, I think British…

David Brooks: I think it was the kind of Jewish… Like, I opened by saying, like, we all know from Fiddler on the Roof, so we saw all these huggy Jewish families, they’re dancing. And I come from the other side, of, the other kind of Jewish family. And the phrase was, “Think Yiddish, act British.” So the super stiff upper lip. Yeah. And my turtles, when I was eight, named Disraeli and Gladstone, which is like, turtles themselves not being the most emotionally expressive animals on the face of the earth, their limbic systems… And so we were like, we had a good, I had a good childhood, but the words “I love you” were not the sort of things that we would we would have done. We, like… My parents were good. Once I got to the point where I could discuss French romantic poetry intelligently, family life got a lot more into… No, we had love in the home. We’re not good at expressing. And so, I evolved—or maybe this was genetic—into an aloof personality type in my nursery school. The teacher said, “David doesn’t play with the kids. He just observes.” And like, I’m four.

Kate: “He will go on to write great observational books.”

David: Right? Well, I tell journalism students, if you’re at a football game and you don’t do the wave, you just sit there while everybody else is doing the wave, you have the right kind of aloof personality type to be a journalist. We just watch people. But it meant a little emotional coldness, like emotional restraint through the first many decades of my life.

Kate: So you could watch emotion without it always, like, pinging anything.

David: Yeah, I just didn’t express it. It was just not part of my repertoire. And, you know, it was an intellectual school in Chicago. I lived in Washington doing policy writing, you know, the most emotionally avoidant place on the face of the earth. So it’s very easy to live your whole life up here [gestures at brain].

Kate: That makes sense to go so fully cerebral. You entered into a journey of deciding to figure out how people connect. What are some of the societal implications of maybe choosing not to be that kind of person or not to be that kind of culture?

David: Yeah, well, I do think we live sort of in an epidemic of blindness. I started to write the book because I was traveling around the country and so many people told me they felt invisible. And these were people like in the Midwest who said coastal elites don’t see me, Blacks who thought that whites don’t understand their daily experience and there were like, husband and wives who really should know each other best, realizing the other person has no clue. And so there’s just so much social blindness, and then it shows up in the statistics. Like 54% of Americans say that no one knows them well.

Kate: That no one knows them well.

David: And the number of people who say they have no, no close personal friend has quadrupled in the past few decades. The number of people who give themselves the lowest happiness rating has gone up by 50%. Like I can speak, all these statistics…

Kate: Wait, tell me that last one again?

David: They rate people. They give you, you rate yourself on happiness levels. And the number of people who rate themselves at the lowest level of happiness, of possible happiness, has gone up by 50% in the last two decades.

Kate: Oh my gosh.

David: The worst stats are high school. So they ask high school kids, “Do you feel persistently hopeless or depressed?” And 45% say they do. And so it’s just one, like, one bit of evidence after another that we’re in the middle of some sort of social, emotional, and relational breakdown. And so there are a lot of things that cause that, social media and stuff like that. But one way to fix it, it seems to me, is we get really good at getting connected to one another. And so, it’s social problems, but it really comes down to skills. Like how do I ask for forgiveness, if we’re friends? How do you offer forgiveness? How do we have a good conversation? How do we listen to each other? How do I break up with someone without crushing their heart? Like, these are skills. And somehow we stoped teaching them. Maybe we never did, I don’t know.

Kate: That was maybe one of the more… Because this, the podcast always ended up being about four themes over and over again. It was about, like, courage and love. And, but one of them is interdependence. And every time I talk to somebody about interdependence, we get a certain kind of mail that is…it breaks our hearts because it’s people saying, I understand the precarity of life. My life is falling apart. My life has become very small and I don’t have somebody. So when you say you’re not alone, I really am alone and I don’t know what to do next. So when we had Vivek Murthy on, who talks a lot about loneliness and so on, he’s like, “Find your three people!” And I, like, from what you’re describing, makes me think, wow. Like, so few people have their three people or know what they would need to do to find them.

David: Or even people you may not get to see a lot, like we’d see each other every few months. But, I feel like I really know you. I feel like, like we have it. And that interconnection is a beautiful word that’s been applied to this limerence when two people are intertwined. There’s a beautiful passage, there’s a man named Douglas Hofstadter, who’s a cognitive scientist, who wrote a book called I am a Strange Loop, and he was—when he was a young academic, he was on a sabbatical with his wife in Italy when their kid was four, and she died of a stroke. And he was grieving her, and he kept her photo on the mantel. And one day he looked at the photo with special attention. And he said that he wrote this (I’m going to paraphrase): I looked into her eyes and I looked straight through her. And I thought of our hopes and dreams for our children. And I realized they were not separate hopes. They are single and identical hopes that had interconnected us more deeply than I ever thought human beings can be interconnected. And I realized that some piece of her was not dead, but had lived on very determinedly in my brain. And so he describes, as a cognitive scientist, the loops that go between us. And some of those loops are, you know, intellectual. But when we’re talking, we’re not aware of it, but we’re synchronizing our breathing. We’re synchronizing our hand gestures, the speed with which we speak. We’re synchronizing our vocabulary levels. If we are talking to somebody who has a different vocabulary, we’ll synchronize. And so human beings just need to do this. Recognition is the first human quest. Like, a baby comes out looking for a face to look at. And so when that’s taken away as a baby or as an adult, it’s just, it’s not only a sense of invisibility, but it’s just a sense of, of sort of deep, social pain. And when you feel nobody’s looking at you, paying attention, you experience it as an injustice, because it is. And then you lash out and you get, you get angry. And we get a lot of anger in the world.

Kate: Yes. That reminds me of that word… I’m never good at the German compound nouns, when they, like “The Germans have a word for this.” I heard it in an interview that the theologian Miroslav Volf was doing with his mentor. It’s Jürgen Moltmann.

David: The Theology of Hope guy.

Kate: Yes, exactly. And he’d been in a prisoner-of-war camp and was trying to reconstitute his sense of self after this youth had been destroyed by his—and alongside his country—and his sense of identity. And we talked about his wife. He used this beautiful word about like, I’m not just seen, but he says, “Well, I’m not….” He was like such an old man when he said it, he was so cute. He’s like, “Well, I’m not loved because I am so handsome…” and like, pauses. So you, like, see his cute little scraggly eyebrows and stuff. But he’s like, “…but when she looks at me, I am beheld.”

David: Yeah, I have this section in the book—you’ve been to our house and you know, my wife, Anne. And I describe what really was a motivating moment for me to do the book. Because I was sitting on my dining room table and I was reading some boring book, which is what I do. And Anne walks in the door, front door, and she stands there in the doorway and it’s the summer afternoon and the sun is coming in behind her. And she hasn’t even noticed me sitting there. But her eyes rest upon an orchid we have on a table by the front door. And she’s just thinking about something. And I have this look, and I look at her, and this was like three years ago now. And I think, “Wow, I know her. I really know her. I know her through and through.” And it wasn’t like the personality traits or it wasn’t the biographical. It was just like the ebb and flow of her being. The harmonies, her music and the, the fierceness, sometimes that comes out with her, or the insecurities or the…the transcendent smile. And it was just such a pleasant feeling. It was almost as if I wasn’t seeing her as I was seeing up from her. And you mentioned this word from Moltmann, which brought it to mind, was the only English word that I could think of that describes how I was looking at her was beholding. I wasn’t inspecting her. I wasn’t observing her, I was just beholding her. And it felt so great. And so it’s really great when somebody gets you when somebody sees you, but it’s also really great when you see somebody else. It just, it was such a delicious moment. And I thought, I want to write about how you get this again. And I would go around the first year or two of reporting the book and just ask people, “Tell me about the time you were seen.” And they were not always extraordinary. It was like everyday things like a woman who operates a homeless shelter and she comes home and she’s exhausted, early COVID, and her husband just sits next to her and says, “Here are the six household tasks I’m going to do for the next six months.” And that was it. But she said, “Oh, he knew exactly what I needed at that moment.” A guy told me about his daughter who was in second grade. She’s struggling. And the teacher says to her, “You’re really good before you act, thinking before you speak.” And it took what she thought was her awkwardness and it turned into a positive. And the teacher saw something in her she didn’t even see in herself. And so he just really said that turned around her whole year. When he told me that story, I was reminded of my 11th-grade teacher, Mrs. Dewsnap, the English teacher. I had said something smart alecky in class, which is what I did. And she says, “David, you’re trying to get by on glibness. Stop it.” And in front of the whole class. And I’m like, on the one hand, I’m humiliated because I’ve been called out. And on the other hand, I’m like, “Wow, she really, really knows me!”.

Kate: She really gets me! Ha! That’s so funny. It is true, even when someone points out… I mean, it takes someone who really knows you to point out when you’re stopping short of your own capabilities.

David: That’s another of those skills they don’t teach, which is critiquing with care. Let’s give somebody a critique but from a position of unconditional regard. And that that really is, that’s just, I mean, these are skills. They’re not like, innate, in any of us. You’ve either got to see them modeled or you’ve got to, like…how do you do that?

Kate: We’ll be right back.

Kate: You have categories for how to know people, you talk about illuminators and diminishers. I want to hear about it.

David: So sometimes, you just meet somebody who, they just pay attention to you and they get you. I mean, they’re curious about you and they ask you the extra set of questions to really know, and they make you feel lit up. And the number one reason we don’t see each other is ego. We’re not interested. The number two is insecurity. We’ve got so much noise going up in the head, we can’t really pay attention. And then we’re self-centered, somewhat. My social psychologist told me about a guy who is on one side of the river and there’s a woman on the other side of the river and she calls out to him, “How do I get to the other side of the river?” And he says, “You are on the other side of the river!” He can’t get in her head, he treats it like he… And so these are the natural sins that we commit every day of just being self-centered and selfish and not really being curious about what’s going on with the other person in front of you.

Kate: Kelly Corrigan said something really helpful the other day to me about how she clicks into that mode if she wants to maybe not … Ego. What else, you were saying?

David: Ego, insecurity, and self-centeredness.

Kate: Yes, and self-centeredness. She, in—especially if you’re feeling busy and maybe you’re toggling between roles, like I’m in work mode and now I’m at home and I’m actually still thinking about this other thing. And, you know, here you are and what am I doing…? And she just asks herself, who am I serving right now?

David: Oh, that’s good.

Kate: I thought that was kind of helpful, because then if I’m sort of whipped up about something else, but I’m actually at dinner. And the answer could be, like, the people sitting next to me.

David: And also, like, the person in front of you is interesting on some subject. Everybody’s interesting on some subject.

Kate: Yeah, they really are.

David: And you can have a fantastic conversation with somebody. With anybody. If you approach it—and I try to walk people through the steps, like, what kind of attention do I cast? How do we just hang out when we’re just getting to know each other? What kind of questions? How do I listen? Then, what do I want to know about you? And I’ve, I’ve learned you can just have great conversations with anybody and…you’re happy about yourself.

Kate: I think I do it, too, when I’m, um—this might be a bit weird, but I do it when I’m kind of angry at somebody? Not to be too specific, but if I, if there’s somebody in my life that I am, like, really frustrated by, then I, or I do one of two things. One is I try really hard to figure out a story about them that I don’t know so that I can kind of go around the version of the story that I already have, especially too, if they’re being frustrating and pedantic about something that I’m like, bleh, okay. Like, you need to find a thing. And then I can, and then I can like it. And then you can kind of get like, then I find I can be like, playful and relaxed again. The other thing I do is I try to find…and it has always felt counterintuitive, but it’s always worked. I always try to find a thing about myself that I can open up a little bit, that maybe I could need something. And it could be something really small, like, I really like… I once told, like, a certain set of people I was having a difficult time with that I liked gummy bears. I’ve gotten gummy bears for 20 years now. So I might need to watch, like, what I decide. But like, to be vulnerable enough to have a need that they can fill. I have found that it creates reciprocity that I get, that at the moment honestly, I didn’t want. But I knew that if I could keep finding a thing about them, and maybe they could find a thing about me that it could kind of keep things moving a little bit.

David: Yeah. I was thinking about this distinction between illuminators and deminishers. And deminishers are the people that never ask you a question and they just, like, stereotype you. And I was thinking, well, can you, an illuminator, convert a deminisher? Can they turn them in? And I hadn’t really thought about it. I think what you’ve just described as a way to do that, it’s much more generous than I would be, like, dismissive. But, you know, I think there, I think there is a way you can get somebody interested, but some people are just not question-askers. Like, I’ll go leave a party and I’ll think, that whole time nobody asked me a question. And they’re perfectly pleasant people.

Kate: I hate that. But, every time I look over at a party, you are also the one asking questions. So next time, I’ll, like, attach a sign to your back. Or, like, “Ask this famous man a question, for the love of God.”

David: Like I said, I was at a bar in D.C. not long ago and I was having a drink alone, which other people see as sad, but I see as research. And it’s happened to me many times, especially in New York or D.C., when the tables are all packed in close and there’s a guy on a date, clearly, and he’s bloviating. He hasn’t asked her one question in 25 minutes and you just want to take your fork and just ram into his neck and say, “Ask her a question!” But, you know, people are insecure. They’re trying to impress.

Kate: I love the fact that you’re very good at telling embarrassing stories about yourself. It is one of the—it is very endearing. And that is also a nice way to be like, how do you want to create intimacy with people? Tell them something kind of really embarrassing about yourself that doesn’t turn out cute. Or like, and then in the end, “And all the people rejoiced.” But you describe the kind of journey you’ve been on from being sort of less emotionally available to kind of a…cracking open period. Have you had people in your life that have been especially beautiful models of how to, like, get in and foster that kind of intimacy?

David: You know, we writers, we work at our stuff in public. It’s what we do. And one of my favorite phrases is “What writers do is they tell other beggars where they found bread.” And so, yeah, I think there was a certain point where I just realized being emotionally closed off was bad for my relationships, bad for my personal happiness, and bad… If you protect yourself too much from the world, then you can’t be affected by all the joy and holiness the world has to offer. And so I felt the need to really, like, explore emotion, really get started. So I did what any University of Chicago graduate would do, is I called neuroscientists and ask them about emotion. I wrote a book about emotion. But it kind of worked. I think it did. And then life happens, you know, parenting, bad things happen. I’ve had some professional humiliations and then went through a divorce. And that was like an emotionally searing phase. And it was about ten years ago. 2013. And, and I was intensely lonely. And I realized I had a lot of work friends, like people I could have lunch with and talk politics, but I didn’t have weekend friends. And if it was up to me to call somebody in a crisis, who would I call? And so that was a period of pretty intense loneliness, which manifested sort of as a burning in the stomach.

Kate: Oh, really? I always feel heart-prickly, and yours is in your stomach?

David: Really? Mine is in my stomach. You know, the thing for me is my stomach, that’s like, hotdogs. And so, but what I learned was when you’re in the valley like that, you can’t pull yourself out. Somebody has to do it. And so I got a lucky break. I got invited to this couple’s home in D.C., and I was accepting all invitations in those days.

Kate: That’s really cute. “Great, when? Super. Now? Awesome. See you at four.”

David: I’m free the next seven nights, I’m good, I’m good. And so they had a kid in the D.C. public schools and that their son had a friend named James whose mom had some health issues and drug issues. And she couldn’t always feed James. They said, well, “James can stay with us.” And so but then James had a friend, and that kid had a friend. So by the time I’m invited over there, there are 15 mattresses on the basement floor, and there were about 40 kids around the table. And so they were there in between the ages, in those days, between maybe 16 and 20 or so? 15 and 20? And so I walk in, and there’s this kid greets me in the doorway, and I reach out to shake his hand, “I’m David.” He says, “Well, I’m Ed,” but we’re not allowed to shake hands here. We just hug here. And I’m like, not the hug-iest guy on the face of the earth. But we hugged. But they come to mind as someone who helped me because their great skill was emotional openness. They beamed love at you and they demanded that you beam it back. And so, mister [gestures at self looking serious] had to be a little more open. And, and so I think that evolved. And so I was willing to be a little, tried to be a little braver.

Kate: It’s funny, too, the relation—I’ve heard a lot from people when they, they’re like in the valley moment, that one of the factors that pulled them up was—seems counterintuitive because you think, well, this is the time in which I need to receive. But actually, it was in giving. Which, that’s a strange alchemy.

David: Yeah, but it definitely works.

Kate: Why does it work?

David: Because we don’t love each other, we love each other, and we see ourselves doing lovely things or love ourselves and we see ourselves, you know? You know, there’s the saying, I have to love myself first before I can love others. I think that’s backwards. That we have to see ourselves loving. And then what feels better than generative care to someone? And so… And I guess to the extent that I was, we were doing things for each other, it felt like I was the mature, grown-up buying these kids, endless bikes and stuff like that. But but they really, we were in it together. I was in a low moment. They were, like, they were all going through their challenges. Yeah. And I think it was because it was, low moments, you, you just have to be vulnerable. There, there is an absolute need to reach out there. You quote Moltmann, I’ll quote Paul Tillich, that he has this line, that moments of suffering interrupt your life and remind you you’re not the person you thought you were. They carved through the floor of what you thought was the basement of your soul and revealed a cavity below. And then they carved through the floor and revealed another cavity below. And so in those moments, you’re aware of the depths of yourself, and you realize that only emotional and spiritual food will fill those depths. And so you’re open. And I used to have, back in my valley days these deep spiritual experiences… Now that I’m happier, I have fewer of them. But I don’t, I don’t know if I’d make the trade-off, that I would make the trade, I’d rather be joyful.

Kate: Well, at the end of this podcast is an altar call. We’re gonna offer you an opportunity to have a very spiritual…

David: Maybe it’ll just make me suffer and then I’ll have another spiritual experience.

Kate: And then we’re going to sing into each other’s eyes.

David: Yeah, that’d be great.

Kate: We’ll be right back.

Kate: Your wife, Anne, is really good at what we’re describing.

David: She is.

Kate: Anne is really lovely in the way that she, like… She kind of expects every person in front of her to be poetry. Like that’s how she treats them. She imagines beauty. And then I think that gets reflected back to her.

David: The phrase everyone uses about her is incandescent. So there’s a light there. And I think what I’ve learned from her is that we think the most important part of getting to know a person is conversation. And that is a super, like—to be a good conversationalist is super essential. But before you get to that, you have to be really good at gazing at the person. You have to bring the right kind of attention. If I bring a cold, or objective attention to you, you’ll feel cold and objective. And, but if I bring a warm and loving attention, you will bloom. And so the story I tell, is I was in Waco, Texas, and I’m meeting this woman named LaRue Dorsey, who was a teacher, a strict disciplinarian. I’m having breakfast with her at a diner in Waco, and she presented herself to me as a strict disciplinarian. She’s like, I love my students enough to discipline them. And I was like, Hmm. And then this mutual friend of ours walks into a diner named Jimmy Dorrell. And Jimmy’s a pastor, a wonderful guy, teddy bear-ish guy, about 60-something. And he, like the homeless, wouldn’t come to his church. So he built a church under the highway overpass, called Church Under the Bridge where the homeless were, he has a homeless shelter. He really is a beautiful, beautiful human being. So he goes up to her, us, and he goes up and grabs Mrs. Dorsey by the shoulders, shakes her way harder than you shake a 93-year-old, and says, “Mrs. Dorsey, Mrs. Dorsey, you’re the best. You’re the best. I love you, I love you.” And this strict disciplinarian turns into a nine-year-old girl with just bright eyes. And, and so the moral of the story is, pay attention to people more like Jimmy and less like me. But the…one point is he’s a more voluble personality than I am. But that even deeper point, and I’m going to say this for people who have faith and people who don’t. So Jimmy’s a pastor, and so Jimmy, when he sees somebody, I hope he sees someone made in the image of God. And when he looks at them, he’s looking a little into the face of God. He’s looking for somebody with an immortal soul of infinite value and dignity. He’s looking at somebody so important that Jesus was willing to die for them. And you can be a Christian, Jew, Muslim, atheist, but having that kind of respect for a person and conveying that kind of respect with your eyes is an absolute prerequisite for getting to know somebody. It’s like, when we meet a stranger, they’re asking, “Am I of value to you? Am I a priority here?” And those questions are answered with the eyes, not with the mouth. And so I think with Anne, she just carries that out there. So with her eyes in a nanosecond, you know…

Kate: I’m an important person.

David: I’m an important person and I’m valued.

Kate: Exactly. You write really beautifully about a friend you lost that you have loved forever and ever and ever and felt despair around it and ability to connect with him in moments that… You wouldn’t mind telling me a bit about him?

David: Sure. So here I am writing a book on how to know a person and my oldest friend in the world, Peter Marks, who I’ve known since we were 11. He’s the… Our whole lives— our whole friendship was based on play. We like, age 11 or age 57, we just played. Basketball. If we were eating, we would play with the food, it was always just play. We just played. And he was … A beautiful marriage, wonderful kids, successful surgeon. Outwardly, seemingly great. And he would have said, “I have a great life. I’m the luckiest guy in the world.” Then at age 57, depression just, boom, it hits him. And we noticed it immediately, like if we were going up to play basketball with him, and suddenly the light was out. And so I’m supposed to be good at knowing how to connect with people. But I was unfamiliar with how to deal with a friend who was in severe depression. And so I did the mistakes. And so one of the mistakes was, “You have a great life.” And so I learned later, like if you’re telling someone they should be enjoying what they’re not palpably enjoying, you’re just like, showing you don’t get it. It, doesn’t, it makes them feel worse because, “Oh, I have a great life, I should be enjoying it.” Then I said, “You know, you used to go to Vietnam and you would do these cataract surgeries. You found them tremendously rewarding. Why don’t you go do that?” And I later learned, giving people advice on how to get out of depression, again, just another sign you don’t get it. And so the only thing I found I could do was just be present. Just show up constantly. And I’m sticking around. And then maybe the only useful thing I did was give them a video from another friend of mine who had suffered from depression, a guy named Mike Gerson. And Mike had very bravely done a National Cathedral sermon on this. And he described his own depression. And he, he described depression as a malfunction in the machine we use to perceive reality. And that, Pete resonated with that, that I’m misperceiving reality, and I’ve got these obsessive-compulsive voices in my head that are lying to me. “You’re of no value, no one would miss you if you’re gone.” And, but I think it has, especially in the beginning of the three years he suffered from that depression, I didn’t know enough about depression to know what he was doing. I did not know that if you have been lucky enough not to suffer from depression, you cannot understand it by extrapolating from your moments of sadness. It’s different. And I did not know what to say. And we make our living with words. And words are supposed to be able to help us solve problems. And words were useless. And so it was a…oh, just a slow education. What … how to show up. And it was not—that story does not have a happy ending. He took his life in April of 2022 after fighting courageously and bravely against this beast for three years. But, you know, we… Part of the process of getting to know someone, or getting to know people is not only knowing them at their high moments, but sitting with them in moments of suffering and being present, just showing that you’re there. And it may not help. And his wife’s love and this is their boys’ love for him poured forth in this time. And but, and he had great experts helping him. Yeah, but the beast was just bigger than all of us. And we went to dinner, like three days before he took his life. And you know, you’re trying to reach him. And it’s just, it’s just hard. And apparently on the ride home, it was heart-wrenching was…it was like, “You guys can talk to each other, I can’t.” And so you get that sense of the isolation he was feeling. Um, but it was, yeah, as I say, it was a very hard lesson in seeing someone. You know the mind, there’s a John Milton phrase, “The mind can make heaven of hell or hell of heaven.” The mind is its own place. And, you know, he was just experiencing brutal pain in ways that didn’t have any obvious corollaries to the world that I’ve seen. And I guess one lesson is when I’m talking to you or I’m talking to Pete when he was depressed. I’m not looking at it. I’m looking at your subjectivity, how you’re experiencing this moment. And it could be radically different. If really want to know you, I’ve got to not know your, your objective realities of your life, but how are you experiencing your experience? I would say one of the things anybody who might be feeling sad, and this is a message I try to get across to people. I don’t know this for a fact. But I believe at the end, on his final day, Pete was, Pete was under the impression he was doing his family a favor. By saying they’ll be rid of the pain I’m causing. And having seen the wreckage…that’s, if you ever think that, that’s wrong. That’s completely wrong. So stick around.

Kate: My dad, my dad was very depressed when I was growing up. And the feeling of being close to the…the thing, the light, the light that is dimming is, uh…it’s hard to stay up right, right next to the wall.

David: Yeah. What do you mean? The light that was dimming, you mean, his mind?

Kate: Like in there, he was incredibly depressed. It only got worse. It only got worse. It only got worse. Then he just retracts into this shell of a version, and then just to stay up really close to somebody who’s suffering and their personality is erased. Depression is such an, it’s such a vicious thing.

David: Yeah, yeah.

Kate: That description of that as perception-altering, and like, the things, just the things we have control of when we’re trying to know and love the people in our life. So what you’re describing is such an intense example of the limits of our ability to control whether other people can know, can know how much we love them and want to see them, and…

David: There were no words that could penetrate what he was going through. Or, they would penetrate it, but there were two of him. There was the one who was suffering and the one who was observing the suffering. And so you could talk to the one who was observing. But, and he understood it intellectually. But, but, he just didn’t feel it. And, you know, I think that’s one of my big takeaways. There’s a theory called constructionism that we all construct our own reality. And that we don’t see with our eyes, we see with our whole life.

Kate: We see with our whole life.

David: And so, you know, if we’re, if you’re an introvert, you see a different room than an extrovert. If you’re a security specialist, you see a different room than a home decorator. But if you’re, have been, wounded, then you see a threatening experience where somebody else doesn’t see a threatening one. And so you’ve always got to, that’s why after that power of attention, that’s why conversation is so important. Because you can’t—we have this thing, “I can take your perspective.” You can’t. You have to ask. If say, “What are you seeing here? What are you experiencing here?” And you have to walk through that conversation. You know, it looks like opening our eyes. You just open your eyes and you see the world. It feels like the light comes in. Yeah, but that’s not how it works here. Your brain is projecting out models based on past experience.

Kate: Yeah, I really do like that study that you were describing. That was like, “How much do you think that you see the world correctly? Do you think…” And you’re like, you think “80%” and it was like 20% of your perception is reality? It’s so funny because it’s one of the only places in which, because I’m a really sensitive person, being able to try to guess other people’s emotions has been really key to me trying to figure out what to know and be in the world.

David: So I have this thing that empathy is three separate skills. So the first skill is mirroring, and that’s really like catching emotion. And then the second is mentalizing: I have a theory based on some past experience, what you’re feeling. And then the third is caring. So being, like, we can say a con man is empathetic. They know what other people are feeling, they just don’t care.

Kate: Yeah. Because this kind of accumulation that you’re describing, like not just information, not just curiosity for its own sake, but wisdom is something I do love about you. And for me and our ridiculous friendship, one of the things I’ve liked about it is when I’m feeling not my shiniest self—like you’re fun to be shiny with because we can argue and talk about books and whatever—but I remember one morning I was just feeling kind of a little bit terrible and I texted you and Anne as was like, “Can I just come over in basically glorified pajamas?” And then like 20 minutes later, I’m at your house, great coffee. And then.

David: I put on a suit.

Kate: I was wearing a tux, a top and tail. And then we all just mostly told embarrassing stories. And I have to say, that was one of my loveliest mornings. So thank you for being the friend who’s willing to see people in their shiniest and in their less shiny. It really, it really is a gift.

David: I used to think, like, I felt I was being a burden on my friends. But now when somebody asks me when they’re going through something, I’m so honored. And so the lesson was that you’re never being a burden. Or almost never, you should never, if they’re your friend, it should never be a burden.

Kate: Well, David, I liked who you were. But I also love who you are. Thanks for being a great friend and for writing a beautiful piece that all of us can follow.

David: Oh, thank you. I’ve enjoyed our friendship and I’ve enjoyed your podcast. And now I get to be on your podcast as a friend of the podcastee.

Kate: If one of David’s greatest gifts, really I’ve seen him do this a million times, he knows how to measure the zeitgeist of our time. It’s just really incredible what he’s able to absorb. But the truth is, when I listen to him now, I think, wow, what he’s seeing and hearing is concerning. The invisibility that we feel, the social breakdown, loneliness, and disconnection, that if we’re not feeling it ourselves, we’re probably noticing the ramifications of it. So perhaps we can all learn how to better connect. To be illuminators by asking better questions. Maybe learning how to apologize or how to forgive. To really see and love the person right in front of us. You know, to practice being human, together. So I thought that might be a lovely thing to bless: that desire to see people. The one right there. All right. Here we go.

Kate: Blessed are we with eyes to see the person right in front of us. Not solely their faults or some future version of themselves or the way they always do that thing that drives you nuts. But as poetry incarnate, as treasures to be beheld. Blessed are you who notice the light in their eyes, or when the light dims. You who scoot up close to their suffering, though you might not have the right words to say. You who bear witness to their life in its entirety. The joys, the sorrows, the unfinished-ness of it all. You who cherish every story, even if you’ve heard it before. Listening without judgment and without haste. May your careful attention be met with others who see you as the same bright light and wonder that you are. As you practice seeing and being seen, may you remember that you, too, are a blessing to all who have the great privilege to know you.

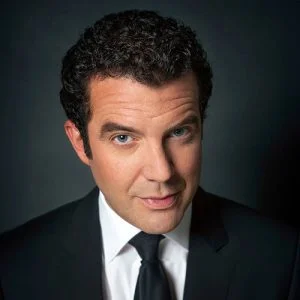

Kate: Well, my loves. If you liked this conversation, would you just make my day and leave us a review? Thank you so much for people who have taken the time to head over to Apple Podcasts and Spotify, it just takes a couple of seconds, but it really does make a huge difference. And honestly, it’s been a source of great encouragement to me and my team. So, thank you. And while you’re there, make sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss an episode like next week. I’m going to talk to a writer. She’s constantly in The New York Times, too. She’s so good. Her name is Margaret Renkl. And we’re going to talk about the beauty of being really alive to the world. She’s really great and funny and kind of just slays me. So you’re going to love her. Oh, hey, my team also put together a gorgeous Advent guide and it is totally free and available now. So if you head on over to katebowler.com/advent, then you can find a really stunning—it’s like kind of a giant free e-book really, that can take you through the preparing for Christmas feeling and season with just a little bit more intentionality. You’re going to love it.

Kate: This is also part of the episode where I get to thank everyone who makes this work, you know, not just possible, but good. Like our generous partners. We have amazing partners at the Lilly Endowment and the Duke Endowment, and they support our great desire to tell stories about faith and life. And I am so grateful to them for it. Thank you also to my academic home, Duke Divinity School, and our new podcast network, Lemonada, where they make—and this is their quote—”Make life suck less.” And of course, a huge shout out to my amazing team who really make everything not just work, but they make it meaningful. Jessica Ritchie, Harriet Putman, Keith Weston, Gwen Heginbotham, Brenda Thompson, Kristen Balzer, Jeb Burt and Katherine Smith. Oh my gosh, I love them and my whole team loves hearing from you. So leave us a voicemail and we might even be able to use it on the air. Call us at 919-322-8731. Okay. Talk to you next week, loves. And in the meantime, come find me online at @katecbowler. This is Everything Happens with me, Kate Bowler.

Leave a Reply