Kate Bowler: “Yeah, but what do I tell my kids?” That is one of the most common questions I get. The bad news has happened. Like you know you’re going to get a divorce or your aging mom officially has dementia or you have the diagnosis. You are just beginning to wrap your brain around something incomprehensible and then in the next moment you think, “Yeah, but what do I tell the kids?” When I got sick, it was the first thing out of my mouth. “Yes, but I have a son.” Zach is five years old now and is approximately 89% puppy with glimpses of dinosaur and ninja and my health is relatively good right now, but the question is the right one. Now that we know that the world is hard and that bad things happen, what do we tell our kids? How do we prepare them for a world that we can’t always protect them from?

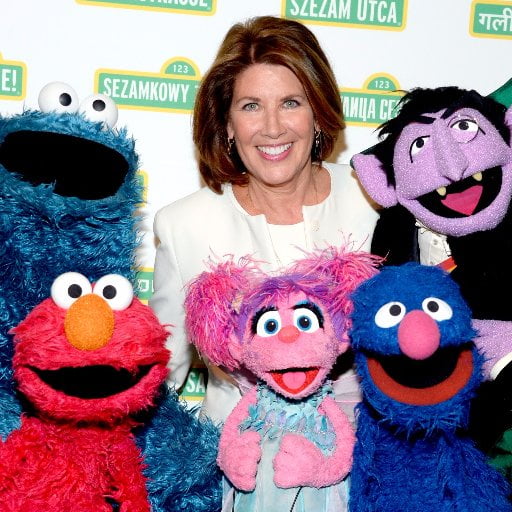

I’m Kate Bowler and this is Everything Happens. Today I want to introduce you to Sherrie Westin. Sherrie is the President of Global Impact and Philanthropy at the Sesame Workshop where their goal is to help kids grow smarter, stronger, and kinder while tackling real world problems. Sherrie, I am so grateful to be speaking with you.

Sherrie Westin: Well, I’m thrilled to be speaking with you. Thank you for having me.

K.B.: This is my dream in part because we’re coming at kind of a momentous moment. It’s the 50th anniversary.

S.W.: Absolutely.

K.B.: I think generationally it’s so important. We all grew up with Big Bird and with Elmo and I’m just wondering, can you tell us, how did this all begin?

S.W.: Well, you know, the origins of Sesame Street are actually a wonderful story. It was 1969 when Sesame Street debuted, as you mentioned, 50 years ago, but it was during the ’60s and the war on poverty. And there was a real sense and understanding of the need to help children with less advantages arrive at school ready to learn. And Joan Ganz Cooney, who is the founder and creator of Sesame Street, the co-founder, had a brilliant idea that television could be used to teach. But not just to teach, but to reach those children who had less advantages and see if that could be empowering. And she and Lloyd Morrisett, who was the co-founder, set out to do this huge experiment. And the amazing thing is that Sesame Street was just an overnight success. You know, she’ll say she never dreamed… She thought, “You know, I hope we’ll have a couple of seasons.”

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: And here we are 50 years later.

K.B.: Was there like a moment of revelation? There’s a story I thought I remembered about a beer jingle.

S.W.: Well there’s a famous dinner party where Lloyd Morrisett and Joan Ganz Cooney were together and he was talking about how his three year old daughter would just sit mesmerized in front of the zigzags on the TV before programming would start.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: And Joan was a public television producer at the time and they started to think, “Well if children can learn jingles, beer commercials, from television, could they learn letters and numbers?”

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: And that was the whole premise.

K.B.: It seems like looking back, it must’ve felt like a new frontier if there wasn’t yet all the sort of developmental psychology to justify this big experiment.

S.W.: I’m so amazed by their prescience because, you know, we think nothing of children’s media today, but at the time the only children’s media on television was cartoons, you know, the Road Runner, or there was Mr. Rogers. But there was no other educational programming and this was the first children’s show to focus on young children, on preschoolers, and they brought together Harvard University educators, incredible creative producers, the likes of Jim Henson for the Muppets, to create this model where the education would be hand in glove with the entertainment. And that curriculum, you know, we still to this day 50 years later… You say that our mission is to help kids grow smarter, stronger, kinder, which is true.

It sounds like a clever tagline, but it’s absolutely baked into everything we do. It’s a whole child curriculum. For children to thrive, they need smarter in terms of the academic basics, literacy, numeracy. Stronger in terms of resilience, coping skills, health. And then kinder in terms of acceptance of differences and empathy and understanding, and this was the first show to have a multiracial cast. You know, they wanted children to be able to see themselves. And one of the other things I think is so interesting when you refer to the science today, A) As I said, they focused on young children and we have the science today to show that those first five years of life are the most important in a child’s brain development and their ability to learn.

Secondly, I love this, they set out to engage adults as well as children. So the reason she hired Jim Henson, the reason there were Muppets, celebrities, humor, parodies is because Joan always felt that the learning would be deeper if an adult were watching with a child, that the learning would then carry on offscreen.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: And today we also have the neuroscience to prove exactly that. The way a child learns is through engagement with a caring adult and, more importantly, for children who are experiencing trauma, the most important thing to mitigate that is that engagement with a caring adult. So it allows us to use Sesame content to really help some of the most vulnerable children.

K.B.: Yeah. What an ecology of learning. That’s so interesting, like in that it informed so many of your choices. Can you tell me a little bit more then about the format? Because I think it would really surprise people to know that it was the first multiracial cast on television.

S.W.: Absolutely. And you know, one of the first programs to show a child in a wheelchair, to have a child with Down syndrome. Again, always helping children to see themselves in a positive light. You know, just a few years ago we’ve launched the first ever autistic Muppet, Julia. I’m so proud of this initiative and, you know, Julia not only helps children with autism have a character they can identify with and feel less alone, but I think as importantly it’s showing all children what they have in common with children with autism and is very direct in sort of breaking down that stigma and increasing awareness and understanding.

K.B.: It’s wonderful to hear you describe it because Sesame Street is such a familiar thing to me, like unbidden or bidden, I can sing the theme song in any situation.

S.W.: And that’s true in places like Bangladesh or South Africa. It’s not the same theme song because it’s local adaptations, but you’ll find that. I love that.

K.B.: I’d love to ask you more about that because I didn’t realize how broad the work of the Sesame Workshop was. This is not just an American phenomenon.

S.W.: No, but it’s also, going back to our origins, is one of my favorite stories because Joan said she thought she was creating the quintessential American show. It was on a stoop in Harlem and within a year we had interest from Brazil, Mexico, Germany, all wanting their own Sesame Street. And that’s what began our international work on creating local adaptations. So it’s not just exporting the US version of the show around the world. It’s Sesamstraße in Germany. It’s Plaza Sésamo in Mexico. It’s Baghch-e-Simsim in Afghanistan, which means Sesame Garden in Dari and Pashto. So while we’re seen in 150 countries, and many of those are our version dubbed, I think the places we’re making the greatest difference is where we have these completely local adaptations so children see themselves.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: It’s the same model, but it’s completely authentic in their language and their culture. Even with local indigenous Muppets. You may see Elmo or Cookie Monster, but you’ll also see Chamki in India or Kami in South Africa or Zari in Afghanistan.

K.B.: I’d love to hear more about the South African version with Kami that you were telling me about. That really struck me as an amazing intervention.

S.W.: Well, we began in South Africa and it was Takalani Sesame, which means “be happy,” and we had been on the air about two years. And again, when we do these local productions, we spend a lot of time finding the right partners, working with education experts there, often partnering with the Ministry of Education. Again, so that we are bringing a certain model and expertise, but learning from those in the country and it’s theirs, you know? That’s really important. So after being on the air just a few years, the Minister of Education said to us that if we weren’t addressing HIV and AIDS, it was a huge problem because at the time, I believe it was one in seven children were affected by HIV and AIDS, either infected themselves or had lost a parent.

K.B.: Oh Wow.

S.W.: And so it really was such an important issue and it affected our audience, young preschoolers.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: So we spent a lot of time with advisors, with others figuring out how can we do this in a completely age appropriate way.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: We created the first ever preschool HIV and AIDS curriculum and that led to creating the first ever HIV-positive Muppet. Her name is Kami. So much thought went into it. She’s a little girl because often people thought that girls couldn’t be HIV-positive. She is very healthy because people often thought, “Well if someone’s healthy they can’t have HIV.”

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: She lost her mother to HIV. So there were opportunities to do stories around coping. And then you also learned you can’t catch HIV by playing with Kami. She was a regular part of the cast, and I am absolutely convinced that Kami saved lives because if you can’t break down the stigma surrounding an issue like HIV and AIDS, then you can’t begin to break down the culture of silence. How can you educate, much less address, an issue if you can’t talk about it?

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: And we had so many AIDS workers and counselors tell us that Kami had made their lives so much easier. You know, we did adult specials. Kami is still on the show. Not every episode is about that because she’s just a regular cast member.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: But I believe we did so much to raise awareness and understanding.

K.B.: Well, I’d love to play a clip if you don’t mind.

S.W.: Oh, that’d be great. That’d be great.

K.B.: So that people can kind of get a sense of what does that feel like in an age appropriate way.

Audio Clip (Musical Introduction)

Friend: Wait, wait, wait. There’s Kami. We can’t go without her. We can’t go without her. Kami!

Friend: Kami! Kami! <Translation forthcoming.>

Kami: I don’t want to play.

Friend: <Translation forthcoming.>

Kami: Because the other children at school don’t want to play with me because I’m HIV-positive. <Translation forthcoming.> They say they don’t want to touch me because they think I will make them sick.

Friend: Oh, but Kami, we all know you can’t get HIV just by touching someone or by being friends with them.

Friend: Kami, we are not scared to play with you because we know that we cannot catch HIV just by being your friend.

K.B.: Oh, I love that so much. It’s so touching,

S.W.: Isn’t it great? And when you think about it, it’s not just reaching children, it’s reaching their parents and caregivers. So you’re enabling them to talk about something that was taboo.

K.B.: Yeah. Well, when you described cultures of silence, you know, it didn’t occur to me until last season of my life how much a failure of language is a failure of connection. And so if you don’t give people the words to use to describe their situation, it’s one of the most isolating things in the world.

S.W.: Well, it’s so interesting you say that because you know, we’re in the middle now of working in the Middle East in the Syrian response region. We have a huge initiative to help refugee children and their new neighbors in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan. And one of the things we’re learning from all of the research and advisories in the region is the biggest need is curriculum to give children those tools and the language to express emotions because they’ve experienced so much trauma and if they don’t have that ability to talk about it, to express it, you know, they act out in other ways. People think of the academics, their literacy, numeracy. But without the social emotional skill, children aren’t able to learn and to thrive.

K.B.: Yeah. And to build the connections they might need if they’re in an isolating situation or they find themselves in a new community where they suddenly have to be transplanted.

S.W.: Well, we were just an advisory in Chicago talking about young children who experienced trauma because of gun violence. It’s really devastating quite frankly. But it’s so interesting to me because the experts are saying what they need, it’s exact same thing I’m hearing in Lebanon and Jordan. So whether a child is displaced or a refugee or they’re experiencing homelessness here at home or traumatic situations like gun violence, the needs are the same in terms of what you need to do to give your children the comfort, the skills, and the language needed to address how they’re feeling at a very young age.

K.B.: You had this other kind of amazing, I don’t want to say experiment, but you had this amazing one in Afghanistan that I’d love to hear about.

S.W.: Well, in Afghanistan, this is a country with 5 million children under the age of five and we know that girls are just proportionately left behind, not allowed to go to school. It’s a huge issue. So in our local production, because girls education and gender equity were big curricular goals, we made sure that the first Muppet that we created was a little girl named Zari. She wears her hijab and her school uniform proudly. She loves to go to school. She loves to play sports. We created a little brother, Zeerak, so that we could also model a young boy looking up to a girl, and the live action pieces will show a father helping get his daughter ready for school. So what I love about this, you’re still teaching the academic basics, but we are modeling for young boys it’s okay for girls to go to school. We’re inspiring young girls at an age when they’re forming their sense of selves and possibility.

And with Sesame, research is a huge part of what we do and so in Afghanistan we’ve tested attitudes of gender equity, and little boys who watch test 29% higher on gender equity, saying they think it’s fine for girls to go to school. And that’s what we have to be addressing, both girls and boys.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: And the other thing I love about Afghanistan is we also had qualitative research among parents. And this is a country where about 70% of the audience is watching with an adult caregiver. And we found again and again, fathers said that the reason they had changed their minds about permitting their daughters to go to school was because of watching Baghch-e-Simsim. To me that’s huge. I mean, talk about planting the seeds for societal change.

And my theory is, you know, I’m not going and telling someone, “You should send your daughter to school”, but because of its children’s show, I think it’s nonthreatening, and yet we’re modeling this. They’re seeing it in those live action pieces. They’re seeing Zari, they’re seeing their children respond. And I think that’s a huge opportunity for Sesame to make a difference.

K.B.: Yeah. Yeah. And kind of unbelievable that something so gentle can make such a dramatic intervention.

S.W.: I agree. But I also think we’ve had a long history of being able to tackle really tough issues from the lens of a child, in part because Sesame Street is so trusted. You know, we’re always putting the needs of children first. That’s why we’re here.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: Also because I think these characters are universally engaging. Right? I’ve been in refugee camps with Elmo and you know, you can’t imagine how children connect with these characters and I do think that, you know, that was one of the things Joan was surprised by.

You know, she realized the Muppets had this universal appeal and they become powerful role models for children and sort of trusted friends. So they really can have influence over young children.

K.B.: And that led you, I mean as a project, to make some pretty bold decisions about how to do curriculum in the states too. I’d love to hear about some of the sort of harder issues that you all decided to tackle.

S.W.: Well the history goes back to when Mr. Hooper died. If you grew up watching Sesame Street, so many people remember this, but what happened was the actor playing Mr. Hooper literally died. And you know, I think, a lot of shows, you would have recast him. And Joan will say that they weren’t certain what they should do, but they really felt they should address it head on and they chose to deal with it directly, and there’s an incredible episode where Big Bird is told, “No, Mr. Hooper died and he’s not coming back.”

Audio Clip

Big Bird: Hey, where is he? I want to give it to him. I know, he’s in the store.

Friend: Big Bird. He’s not in there.

Big Bird: Oh. Then where is he?

Friend: Big Bird, don’t you remember we told you? Mr. Hooper died. He’s dead.

Big Bird: Oh yeah, I remember. Well, I’ll give it to him when he comes back.

Friend: Big Bird, Mr. Hooper’s not coming back.

Big Bird: Why not?

Friend: Big bird, when people die, they don’t come back.

Big Bird: Ever?

Friend: No, never.

Big Bird: Why not?

Friend: Well, Big Bird, they’re dead. They can’t come back.

Big Bird: Well, he’s gotta come back. Who’s going to take care of the store? And who’s going make my bird seed milkshakes and tell me stories?

Friend: Big Bird, I’m going to take care of the store. Mr. Hooper, he left it to me. And then I’ll make you your milkshakes and we’ll all tell you stories and we’ll make sure you’re okay.

Friend: Sure. We’ll look after you.

Big Bird: Well, it won’t be the same.

Friend: You’re right, Big Bird. It’ll never be the same around here without him. But you know something? We can all be very happy that we had a chance to be with him and to know him and to love him a lot when he was here.

Big Bird: Yeah.

Friend: And Big Bird, we still have our memories of him.

Big Bird: Oh yeah. Yeah. Our memories, right. Memories, that’s how I drew this picture, from memory.

Friend: That’s very good. Yes.

Big Bird: And we can remember him and remember him and remember him as much as we want to.

K.B.: There are so many honest things that happen in that moment that kind of blow me away. Like when they say, “No, never,” like there’s a finality to it.

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: And then just leaving enough space where you can breathe into a terrible reality that sometimes you have to repeat for a kid who doesn’t always land on it.

S.W.: Well it’s so important to be honest and concrete with children. I mean, I remember telling my son that we were putting our dog to sleep and, you know, telling him for weeks, “You don’t have to be there in person, but you can if you want.” And then, you know, when he decided he wanted to be there, he said, “Yes I do, but when are we going to wake him up?” And I realized, “Okay, you need to be able to say he died.” Or you know, putting to sleep, passing on. Children don’t have the same understanding of those terms. And it’s so important that we are honest with children, but you notice also how they then talk about, “But we are all here for you.”

K.B.: Yeah. Those little things.

S.W.: Those are so important to be able to emphasize that you’re surrounded by others who love you, and we always have our memories and, you know, there’s so many lessons in that.

K.B.: It was so dumb, but this last weekend Zach had a snake for one day that we found in the yard and he named him Slid. And then Slid was the unfortunate recipient of care and we were trying really hard to teach Zach to be gentle, but Slid passed away, which was so terrible. And then he-

S.W.: You had to say he died.

K.B.: Yeah. And then we did. We had to say he died and it was so bad because I kept stumbling and I realized how emotional I was getting because I feel like I’m always practicing. Like how do I be the kind of parent who says the hard thing in case the hard conversations have to keep happening in our family. And to be like, “Oh no, he is not sleeping. Slid is dead.” And then, “Yes we can bury him,” you know? “Yes we can say a prayer for Slid, but no, he is gone.” And there was so many… We had to return to it so many times, and it was funny how much practice it was for me saying the words as it was to just watch him try to learn the categories.

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: Because you think you have it and then all of a sudden you’re saying, “Slid has gone to a better place.”

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: The other issue that I thought you tackled head on was homelessness.

S.W.: We have a program called Sesame Street in Communities where it’s not just the show, but we’ll create content and we work with partners on the ground who are reaching out to vulnerable families and children. And we provide them with the content and training and tools and we learn from them what they need more of, content on helping children deal with a parent who is incarcerated, helping children who are experiencing homelessness.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: I mean you can’t believe it’s 2.5 million children in the US are experiencing homelessness.

K.B.: Well let’s listen to that clip cause I thought that was a really touching way to get at it.

Audio Clip

Lily: I don’t… I’m not sure I want to paint anymore. Doesn’t really feel like a rainbow kind of day.

Friend: Lily, Elmo and I are your friends and we’re here for you for anything you want to talk about. Anything at all.

Elmo: You know, Lily, sometimes when Elmo talks about his feelings it makes Elmo feel better.

Lily: Well, it’s just that my bedroom is purple and purple’s my favorite color and it reminds me of my bedroom. And we don’t have our own apartment anymore, and we’ve been staying in all different kinds of places.

Friend: Lily, no matter where you are, always remember, the thing about home is home is more than a house or an apartment. Home is really where the love is.

K.B.: “Home is where the love is,” is the most basic and beautiful thing you can say to somebody, anyone in transition.

S.W.: Right. And listen, the other thing I learned from that initiative is to say that a child is experiencing homelessness rather than it’s a homeless child. Because otherwise it sounds like I’m defining you as homeless and it’s permanent. Experiencing homelessness shows that it can also be very temporary or transient, which is so important.

K.B.: Yeah. Yeah. And also that, I mean, so many times in life, we’re just trading places. So a label that someone might wear in one minute, they won’t be wearing in the next.

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: The grace with which you handled these kinds of things was especially meaningful to me because in the middle of my especially terrible season, I got a package from you in the mail and we didn’t know each other yet.

S.W.: No, because I read your book and I was so moved and I was particularly taken with… I think Zach might’ve been two at the time?

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: So I thought, you know, probably Zach likes Sesame Street, maybe I could send some Sesame Street things, and I didn’t know if it would reach you. So I was so happy that it did when you reached out later and now here we are. Who would’ve thunk?

K.B.: Well it was so beautiful. It was so kind to me and then it also gave me something that I could use which was this beautiful book called the Comfy-Cozy Nest. The Comfy-Cozy Nest is like the cutest picture book ever. And in it Big Bird is having like big feelings, and Big Bird is offered some suggestions of things to do, like have little lovies and stuffies around him or have pillows and kind of like make his own safe place, like his own comfy, cozy nest.

And that was so beautiful for me to feel like as a mom I was giving my kid something that could help him feel safe. And also really struck me as one of the big premises of the Sesame Street project is that you can let kids have big feelings.

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: And it’s still somehow okay.

S.W.: Absolutely. And that it’s important for them to understand that it’s okay.

K.B.: But it did sort of open up a question for me that I kind of feel like I’ve been waiting to maybe address myself is just, how do I talk to Zach about my illness in an age appropriate, you know, like in an age appropriate way? It feels like an unfolding question, in part because I feel inadequate to answer it sometimes. People always ask me like, “How do you say it in the right way?” and the truth is he was so little when I was first diagnosed and then, in part because of my personality and also the nature of my situation, so much of it happened kind of offstage where I could go away and get treatment and then come back and sort of seam indestructible.

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: And I realized that unless I learn along with him about how to do a good job in this, he won’t learn unless I explicitly learned to bring it up. So your work really resonated with me because I thought, you really believe, like you really believe that little people can handle the big stuff.

S.W.: Well, yes. Listen, Sesame has an incredible staff of child development PhDs and experts. I’m certainly not one of those, but I think in your instance you are right too. That was not something he could comprehend.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: I’m so glad you’re doing so well. You look beautiful. People can’t see you who are listening, but you look great. But I do think that it’s important to be able to say things like, “You know, mommy is still sick but so many people are trying to help me be well, to get better.” You always also want to be very reassuring and I can’t even imagine how hard it would be if when you think, I think what you’re saying is, “What if there’s a point at which I have different news?”

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: And again, depending on the age, it would also be about reassuring your son how many people are here for him, how much he is loved.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: How much you will always love him and this is really hard and I’m not the expert but-

K.B.: Well I always feel like that too when people come me, yeah.

S.W.: But I do believe you can be honest and still incredibly reassuring.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: And that’s really important.

K.B.: Yeah.

S.W.: At the same time, you don’t want to frighten children. You always want to give them that comfy, cozy space.

K.B.: Yeah. Because as a parent, you know, like your body is also a home. You know, it’s a place people go to feel safe and loved and understand where they are in the world. And I mean with so much, I guess, so much to do with uncertainty is you’re never sure how to frame something that may or may not happen. So I mean the news, I might always be fine-

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: And so that might be irrelevant.

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: But I don’t want to be the kind of person who doesn’t want to learn to be better as his questions change and evolve.

S.W.: Right.

K.B.: I guess I just, saying this as a parent, but the premise of your project is that we really all can learn to be better for them.

S.W.: Absolutely. Listen, the most important thing and the incredible gift you have given Zach, as I said, the first five years of life are the most important in a child’s development and the most important thing is engagement with a caring adult, and Zach is clearly loved and surrounded by people who love him.

K.B.: I guess talking to you, it reminds me how much all of this and the work you’re all doing is kind of an experiment in being human. Like, you know, good things can happen, bad things can happen, but even among the smallest of us, if you give them a few tools and then a lot of love, people really can make it through.

S.W.: Absolutely.

K.B.: Man, I love that and I’m so grateful to be talking with you.

S.W.: Well, it’s such a treat for me, so I can’t thank you enough for reaching out and for asking.

K.B.: Thanks so much.

I was dropping Zach off at school recently and his very favorite teacher was in the carpool drop off line. He jumped out and said these three things to her:

I got this haircut!

My snake died!

I love your forehead.

He was totally right. She has a great forehead. But the things I loved the most is how honest he was. He was pretty gutted that the snake he had known for one day, which he named SLID, had died. And he let all his colors show.

Everyone is so afraid to tell the truth. But maybe kids are the best truth-tellers of all. And with tools like Sesame Street and the work of the Sesame Workshop around the world, I love the idea that we are all part of a great experiment. Can we handle a little more? If told in love and gentleness, can we show all our colors? And let other people show theirs? We are used to saying, I can’t handle it or, oh, they could never handle it. Wait until they get older. But there’s a chance that, with a little help, we can have a little more faith in each other…and a little more grace for ourselves.

This episode is made possible by our incredible sponsors, North Carolina Public Radio WUNC, the Issachar Fund, the John Templeton Foundation, the Lilly Endowment, Faith and Leadership: An Online Learning Resource, and Duke Divinity School. And of course my team. Many thanks to Beverley Abel, Jessica Richie, and Be The Change Revolutions. I’d love to hear what you think of this episode. Write a review on Apple Podcasts and find me online @KateCBowler. I’m Kate Bowler and this is Everything Happens.

Leave a Reply