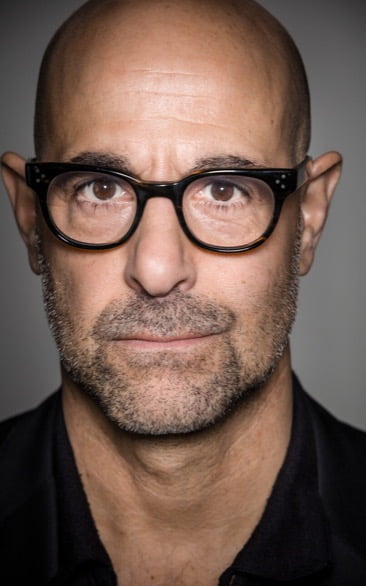

Kate Bowler: There are seasons of our lives where nothing comes easy. There are no slow sweet mornings or dawdling afternoons or rambunctious evenings where you don’t know how things might end. No, things are pretty buttoned up. This has to be done. That has to be finished. Life is small and tight. People have to be cared for. Work has to be accomplished. Or maybe you can’t do much of anything anyway because you’re recovering from something, not able to get much traction or waiting for a yes in a season of no. And when life is too small, so often our pleasures dry up. We have been in a long stretch of pandemic deferment, putting off experiences because they weren’t safe or were impossible. Unable to choose much of anything. But sometimes when we can’t go wide, we learn to go deep. We dig out our small delights, the pleasures we can reach for here today, where we are in our small lives, which are in desperate need of beautiful things to sustain them. So today, let’s linger here for a moment. Take out a napkin, lay out a nice tablecloth and sit down for a moment with our absolutely delightful guest who is excellent at making his tastebuds widen his world. The shockingly here with me today, can you even believe it, Stanley Tucci. Of course, Stanley Tucci needs no introduction, and yet I will forge on describing him as if in a fugue state, he is an actor, producer and writer. We loved him in The Devil Wears Prada and Julie and Julia and The Hunger Games, just to name a few. He also hosted the mouthwatering food and travel documentary series on CNN called Stanley Tucci Searching for Italy, which you must watch. And his latest work is a gorgeous memoir. I adored it, and I cried and laughed on the plane. It’s called Taste My Life through food. Stanley, I cannot believe you are here. You bring me joy. Thank you so much.

Stanley Tucci: Oh my god. OK, thank you. That’s the best introduction ever. Thank you. I’m so happy to be here. Thank you.

Kate: I will keep it as a voice memo. You can play at any time.

Stanley: And what you what you wrote prior to my introduction. I mean, that very beginning bit there was just gorgeous.

Kate: Thank you. Well, when I started reading your book, I immediately fell in love with your family. This modest family who prided themselves in simple joys like your grandparents wine cellar with wine that may or may or may not have been the best wine in the world.

Stanley: Yeah, yeah, it was, it was tough. But,

Kate: Hah the wine?

Stanley: But we loved, we loved it. I mean, oh yeah the wine was tough. I would I wish I could have it again. Yeah, because it would mean my grandfather was alive. So yeah.

Kate: They were resourceful, if you don’t mind describing the kind of absolutely delightful resourcefulness they had about making something into more to put on the table.

Stanley: Necessity is the mother of invention, and I think the southern Italians in particular, so many Italians, but I think particularly southern Italians, because they were so incredibly poor, we’re able to make a lot out of practically nothing. When you see the dishes, so many dishes of southern Italy, there are so, so very simple and yet they sustain you. Even the dishes of Tuscany, which we think of now as a very wealthy place, and it is more wealthy than a lot of regions in Italy, but it wasn’t always. There were pockets of wealth in the urban centers, but the people in the countryside were incredibly poor. Therefore, their diet was beans and kale. You know, I mean, and that was it. I mean, I’m sure they had terrible gas, but it kept them, but it, you know, it sustained you, and even the bread was was made without without salt. Yeah, because salt was very dear. So it’s that kind of stuff. And just to see my grandparents, you know, nothing ever went, went to waste and they grew their own so many of their own vegetables and they had chickens from time to time. They had rabbits. When my mother was young, they had more animals than when I was young. But all of that stuff went onto the table. You know, from nose to tail, from root to flour, it all ended up in your mouth.

Kate: That’s right. From tree to squirrel. From squirrel to pot.

Stanley: From tree. Yeah. Yes. My grandmother eating, ripping apart a squirrel one time. I couldn’t believe it.

Kate: You would be wonderful with Mennonites. I grew up around Mennonites, and especially during the pandemic, they’re absolutely inexhaustible resourcefulness came out and my brother in law has been making mead, which is truly horrific. So many, he’s so pleased and there are so many jugs and there’s like a mead cellar which the dog fell into the other day. But it’s just it’s a lot happening.

Stanley: Mead is from honey, right? Isn’t it based, honey based?

Kate: It is honey based and it belongs in the medieval era from whence it came and it should be retired?

Stanley: Yeah, I’ve heard that. I’ve heard that.

Kate: Yeah, whenever I see the big jugs of anything coming out to be to be tasted, I think. Thank you. Thank you for your generosity. Your grandparents families were, as you said, immigrants. How did you see them recreate their culture in the ways that they cooked and prepared food? They were, they were kind of always at home, even if they weren’t still at home.

Stanley: Yeah, yeah, exactly. I mean, one of the things having done just a little bit of work with UNHCR, the United Nations refugee organization, they one of the things we talked about is. That what the one thing that people can bring with them when they’re the refugee, are there recipes? Because those recipes are they’re in your head, and they’re in your mouth? Yeah. And to be able to start there is as a way you begin to recreate the home that you’ve had to flee, either for war, pestilence or war. In my grandparents case, it was the lack of opportunity, yeah, and real poverty.

Kate: It is kind of amazing when you can walk into a house and just by the smells that you know where they’re from.

Stanley: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. Yeah. It was so funny. It was the other day I was walked into my room, I walked into one room in my house here and it smelled exactly like my Uncle Frank’s house, and I don’t know why, I don’t know what it was, I don’t know what made it smell that way and I couldn’t figure it out. Yeah, I couldn’t figure it out. But there are those smells like my grandparents, my mother’s father’s house parent’s house smell specific, very specific, that smell. And a lot of it just comes from what are you cooking? I mean, and there’s nothing worse than walking into someone’s house and they just they don’t cook and, you know, you’re not really smelling like the diffuser.

Kate : Yeah it smells like the diffuser. It’s lemon grass. Yeah, I yeah, I always when I walk into my mom’s kitchen, I can always, she has this lovely little garden and we live really close to a river in southern Manitoba, where the soil is really, really rich and everything grows unbelievably quickly because there’s really only a two and a half month summer. And so it goes from snow to the flooding season and then the introduction of the hanging worms and the mosquitoes. But somewhere in there, there’s an instant garden and the taste of carrots. I mean, pulled out of the ground, carrots is one of the strongest things I associate with my mom.

Stanley: Yeah, I remember having carrots right out of the garden, my grandparents grew them, and they were incredible. Yeah, I mean, I’d be hard pressed to find a carrot that tasted like that today. Yeah, even the ones that you get at the farmer’s market and they’re organic and they’re blah blah blah. But I don’t know, there was just something about, yeah, I don’t know what that is.

Kate: I guess one of my favorite things about like being from somewhere, and I associate Manitoba with these really fast growing summer gardens and lots of winter food like, you know, even later on, it would be like bison burgers and dried elk and but these small joys and the taste of it, the familiarity of it, and I love that you have such a intense, I mean, you’ve been to all these beautiful restaurants, but you you put in these huge plugs for how unfussy our lives can be. I did really enjoy that doubling down on learning to be unfussy came to you at quite a cost when you were with, you tried to order something unbelievably, maybe too french with Meryl Streep that turned out to be more french than you intended.

Stanley: Oof, oof that was tough

Kate: Andoueillette? Is that what it is?

Stanley: Andoueillette. So Andoueillette, now Meryl and I, we went to the Deauville Film Festival, which is like a great festival. And there’s great food around there, and it’s just fantastic. So then we were heading to Paris to do a press junket in Paris for for Julie and Julia. And it was the first like sort of real press jump and stuff I’ve done since my wife had passed away, but I was like, I was so happy I was with Meryl and I felt, you know, comfortable with her, and it was just it was it was great. So we go to this place, one of the drivers says we go to Normandy, we go to the beaches of Normandy, we get a tour. The guy completely ignores me and everybody else who just wants to tell Meryl everything. But it was still very exciting. So then we’re going to stop for lunch, before we get to Paris, because it’s like a two and a half hour drive whatever. So he says, we stop at this little place in beautiful little place, very unpretentious, sat outside and we ordered the andouiellette, yet because we thought we liked and we sausages. So we thought, Oh andouillette, like small, ette, small. So it’s a small aundouille sausage and we have to at them. So we get it and they bring it. And I don’t know what I can say on your podcast but I’ll say

Kate: Yes, you can say all the things.

Stanley: Right? They brought a thing that looked like a horse cock and put it on our plate. They just brought it to you on a plate and you’re like, we thought looked at it, Meryl’s brother was there, too, and we looked at him and was like, That’s interesting. It’s not what I expected. And then we took a bite and almost projectile vomited because I give the Wikipedia definition in the book of andouillette, which is, do you have it?

Kate: I do!

Stanley: Great! Read it! Because it’s better if that is the only way to say it

Kate: Andouillette is a coarse grained sausage made of pork and occasionally veal chitlins, baguette intestine, close bracket. Yeah, pepper, vine onions and seasoning. Tripe, which is the stomach lining of a cow, is sometimes an ingredient in the filler of an andouillette, but it is not the casing or the key to its manufacture. True, andouillette will be an oblong tube. It will be made with the small intestine. If it is a plum sauce, it’s generally about 25 millimeters in diameter. But often it is much larger, possibly seven to 10 centimeters in diameter and stronger in scent when the colon is used to. True andouillette is rarely seen outside friends and has a strong, distinctive odor related to its intestinal origins and component. Components in such a horrible word for food.

Stanley: Yeah, components!

Kate: Although sometimes repellents to the uninitiated, this aspect of undo it is prized by its devotees. And yet it was not be treasured, apparently, in the way it was meant to be intended.

Stanley: Oh, my God, it was so horrible. And they’re just I don’t even know if they’re like cooked. I don’t even I don’t get it. It’s so – sausage is like one of the greatest things in the world, but not that. And I had I remembered hearing about it once I ate it, then I remembered all those like, Oh yeah, I saw a show on this one. I saw, you know, but I didn’t you know. But we did laugh.

Kate: I think I think it is, I mean, one of the one of the greatest parts about experiencing you experiencing food is either the like you are in a torrid love affair with it. You are going to run away together, like when you describe cheese, like, for example, you have this quote where you’re like, you’re you’re talking about cheese, just cheese, just cheese living its life by itself on a plate. It’s soft and gentle creaminess when melted just wraps itself around. OK, I’ll have to take a cold shower. I love that. I love the pornographic attention to the love of it because you decide to either really love it or really hate it, or really have a lot of opinions about when you eat bread.

Stanley: Oh, absolutely. You cannot, you may not. Eat bread with your pasta. So when you’re eating a bowl of pasta, if you eat bread with it, it’s that’s just heresy. It’s just don’t do that. But when you finish the bowl of pasta, you take a piece of bread and you use it as fare la scarpetta, which means a little shoe. And with that little shoe, you pick up the rest of the sauce, and that’s fine.

Kate: And that’s fine.

Stanley: Otherwise, no.

Kate: Otherwise, you are dead to me. Whatever we had is lost.

Stanley: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Even if I didn’t know you, yes.

Kate: Yes, yes. You have to feel yourself at this moment being cut off from the universe if you were to transgress some of the laws. There’s a lot of rules that you give. I don’t often read a list of ingredients that includes the term fuck ton of butter, but I did laugh very hard on an airplane and feel as a pretty deeply spiritual person that I was not allowed to share that. But I think it’s just it’s so choosy in such a fun way because it’s all these things are available to us to be picky about. If it brings us joy.

Stanley: And there’s nothing wrong with being picky, it doesn’t mean you’re snobby. It just means that you respect quality. To be a snob, a snob is someone who just, you know, I only eat at Michelin starred restaurants. If you’re like, what’s that mean? Yeah. What’s that even mean? I don’t eat blah blah blah. I don’t. I only drink Chåteauneuf-du-Pape, you know. It’s like you’re an idiot.

Kate: I think what I love to about it is it feels like you being picky is about you wringing the last drops out of a lovely thing where you’re like, No, no, no. Let’s try the let’s what if we took our martinis and we just gently stirred them and we lovingly, we do not shake them. We we choose something. And then the choosing, at least for me, it gives me like a little rush of pride and a little feeling that my, my day just got a little, a little elevated.

Stanley: It makes it your own. You’re personalizing it. Yeah. And I think food is a personal thing. I think cocktails are a personal thing. Yeah, you have a recipe, but then I don’t know. Do you like it up or do you like it on the rocks? Do you like a little more gin in there? Or do you like a twist? Or do you like a twist and an olive? Yeah, whatever. OK, what do you like? And then why do you like that? Yeah, that’s also the key thing. Why do you like it? Yeah. Why do you like it? Twists and an olive together? What is that in your mouth that tells you that that is good? That’s that’s what’s interesting to me, and that’s what sort of separates the men from the boys is the why. Yeah, you can go, Oh, give me this and give me that, give me this. Yeah, but why? Yeah. That’s what I want to know.

Kate: Yeah, I I’m just thinking of your absolutely adorable viral cocktail tutorials during the pandemic and how fancy it made me feel. I’m just thinking of that of why that of the why of that. Because I think at least when your day is stripped down to the studs, when you have very few lovely choices, being able to sit down and enjoy something and then enjoy enjoying it, it’s like, ask yourself the the why of it. Does this taste clean? Does it taste fresh? Does it taste- after chemo, I lost most of my taste buds.

Stanley: Oh wow, yeah.

Kate: So I lost a lot of the the pleasure that I could see other people enjoying and learning to sit down just to give myself like a minute to practice enjoying things again was, I don’t know, it made me feel a little bit more human, even if I didn’t have that many choices to make that day.

Stanley: Do you, have you regained it?

Kate: A lot of it, and part of it is because I’ve learned how to describe things. I mean, it kind of feels like shading in a drawing, were I to actually be good at drawing, it feels like I’m kind of learning like, oh, I knew the rough contours of something called sour, but now I can be like, oh it what are these, what is the is it an apple? Is it a- is it a-

Stanley: So it’s it’s almost back or almost completely back or.

Kate: Yeah, it’s slowly coming back. It gets better. Yeah, it gets better. The more I practice is how I feel. Yeah.

Stanley: So yeah, no, it’s true. It’s true. It took me a long time to get it back.

Kate: I know you had a long, a long arc of that yourself as you had lost the ability to taste with a really harrowing experience. If you don’t mind telling me.

Stanley: No, no, it was the high dose radiation. There was a tumor in my throat, so the high dose radiation was the only way to cure it. Luckily, it had not metastasized. I had been misdiagnosed for two years, which was unfortunate, so the tumor was huge, so they couldn’t operate on it.

Kate: Wow.

Stanley: So they just had to do, I guess, radiation chemotherapy, which increased the efficacy of the radiation. So the thought what that does is it destroys your taste buds, destroys the inside of your mouth and your throat and your salivary glands. So I still don’t have all my saliva back. And you know, I always have to drink water. I still can’t eat things very sort of quickly. You just want to grab a sandwich that’s like, not that. Yeah, that’s that’s like a full time job to eat a sandwich without dipping it in something. You know, I had a croissant this morning after after a doctor’s appointment, and I have to get a cup of coffee with it. And dip the croissant in it to eat the croissant, yeah, and then drink water with it and everything like that, yeah, yeah. But it’s OK because listen, compared to the way I was three years ago, after that treatment. It’s fine, and I can smell everything and taste everything again, and the taste is the most important thing for me. It’s not so much being able to finish the thing I’m eating as long as I can taste it.

Kate: Yeah, yeah. We have a lot of people here in this community for whom food stops being a pleasure and starts being an obstacle because of because of surgeries, because of illnesses of various kinds, or sometimes just because they’re in a caregiving position. And they’re they’re kind of worn out doing the feeding and the caring for someone else.

Stanley: Yeah, like you were saying.

Kate: I wondered, if there was a like a grief associated with when you were first diagnosed that that all of a sudden like the the joy of food was just gone.

Stanley: That was my biggest fear. I mean, they assured me that I was going to live and make it through. They couldn’t really assure me that I was never going to- that I was going to taste again, whether I’d be able to eat properly again. They did their best. But they were like, look. Most likely. Yeah. You’re going to do fine. You know, most likely isn’t always the greatest way to start a sentence. So, so that was hard and it was really scary and I was depressed and I was nervous. Also, of course, nervous. And I still am about, you know, you know, this feeling it, you know, how long is it going to come back? Is it, you know, all this stuff? And you know, it’s all exacerbated and heightened by the fact that my first wife died of cancer. Yeah. So watching her, traveling around the world with her, trying to find the cure, whether it was standard care or alternative, was a real education for us both, but ultimately, in her case, futile. So, that’s scary. I didn’t want. My kids to lose both parents. And I wanted to get to know my younger kids. So it was all scary. Still scary. And yes, so grief, yeah, you’re grieving for what you might lose and you’re grieving still for the person you lost.

Kate: Sounds like that was a long, a long stretch like a probably seemed endless season of practicing hopefulness around her cancer and then looking for treatment and then the not- the not knowing is kind of a different path than the one where there’s just kind of a fixed diagnosis. They’re not, you know, of course, better or worse, but it’s just I always found that that kind of prolonged uncertainty is makes makes hope a really beautiful and painful thing all the time.

Stanley: It doesn’t, but I found it just so frustrating. Anger, you know, I’m still angry about. I can’t always let it go, you know? Kate’s struggle and her death and also, you know, what happened to me, I’m like pissed off about it. Yeah. You know, I am, I’ll always be, I’ll always be, and that’s probably not the greatest place to be in the world, but it’s always going to be there, yeah, there are certain aspects of it that you let go of and you will say it’s OK, I’m I’m here, I’m alive. And she was a wonderful person and you know, she had such a great impact on people. But I mean, on the other hand, you’re like, Well. She’s not here. How come that guy still alive? You know what I mean?

Kate : Oh, yeah. Oh, I know exactly. Yes, that guy. Yeah, yes, I totally agree. A couple of names immediately come to mind.

Stanley: It’s a terrible thing to say. How come that guy’s still alive? You know, he’s horrible, a horrible person. Why did she die? Why did that guy get sick? Why can’t – he’s awful? Yes. Why doesn’t he get cancer? You know, it’s terrible. It’s a terrible thing to say, but you cannot, and no one can deny that they don’t think it.

Kate: I could not agree, no, see as a very spiritual person I can’t relate to those who cannot relate to those dark sentiments. I’ve never I’ve never pointed at people. I’ve never pointed at someone in New York City, a stranger and yelled you’ll be fine. Oh, and I was feeling indignant. Feeling indignant. I yeah, I guess that’s what I love about the, I mean, it sounds like you push out into anger. I kind of collapse inward into sadness and shame, which is another great choice if you’re interested in just a variety of of responses. I’ve tried to shame, but I I have found it hard sometimes to to both be honest and then to enjoy the place in which I find myself without quite so many explanations like, all right, then things being as they are dot dot dot universe comma.

Stanley: Yeah, yeah.

Kate: What are the what are the non bright side gifts I have today? And I guess that’s partly why I feel so grateful when I see people protest the irony of life by really seizing on to fun and lovely things and your, yeah, homicidal approach to noodles is just I couldn’t stop. I couldn’t not love you for that! Because it sounds like I’m immediately that what you do is you, you grab, hold you, you grab hold of your people, and then you gather them around something. It sounds like you’re wonderful at that impulse. You can’t just have a pizza. You insist on having a pizza oven and a place where people can have paella outside. You’re like, I’m not just having a dinner, I’m having 200 people over, and then I’m going to scale this food. I’m going to make a lot more of it, and I’m going to be picky about it at the same time. You’re stubborn gathering impulse seems really wonderful.

Stanley: Yeah, I have that, Felicity has that, too. And sometimes we both go, what are we doing? We’re so tired.

Kate: Why are we having another party?

Stanley: I can’t do it because also we’re here in London and now the pandemic is, you know, hopefully on the wane and things are getting back to normal to a certain extent. So you want to have people over and because you have kids like you can’t go out to dinner every night, you know you, I mean, you never see your kids you’re not at home. How many babysitters in the world are there? You know, so you’re like, you don’t want to go to dinner, I want to be home. Yeah. So, you know, we and also in London, you know, London is such a mecca now for the film and television industry that everybody’s working in. So I have friends who are coming over from America who are just there, just standing there for like six months working on a project. So it’s always like those kind of and you know who’s in town, you know who’s in town? All right. Come on over, come on over. And then you’re like, after a while, you’re like, Oh my god, again.

Kate: So you rent a hostel, a beautiful, just really upscale hostel.

Kate: You seem to experience love and food and the moment very intensely and so, so many of your stories are just are stories about being in love with people and appreciating them, just kind of wrapping it up in a big, long, lingering meal. And you tell this beautiful story of when you had fallen in love and married the beautiful and brilliant and very British Felicity and you’re trying to combine your lives. And she is a very obligingly and exactingly taking on cooking and traditions of yours. I wondered if you might tell me about her attempts to make her own version of roasted potatoes and live her own life.

Stanley: So when she said roast potatoes, I thought you meant roasted potatoes. It’s totally different. Well, I thought being Italian, I thought, Oh, well, she’s she’s going to, you know, just cut off the potatoes like we do in this, you know, because we had put this together. She goes on, makes the roast potatoes. So you cut them up, you put a little olive oil, garlic, some onion and if you want, you know, rosemary, thyme, whatever and roast them in the oven. So she starts cooking one night and she takes these potatoes, she peels them. And and boils them. Like big great big potatoes. And I was like, what are you doing?

Kate: I like how concerned are you right now. Yeah. Because you’re like, I know this terrible thing to tell you about what she did.

Stanley: Yeah, no. She’s boiling things. I was like, What are you doing? I think you’re making roast potatoes, she goes I am. I go all right. I mean, I don’t know. I thought boiling was different than roasting, but silly me. So then she takes like a layer of a layer. I don’t know, like a whole bunch of goose fat, or vegetable oil I can’t remember, and she lines a baking tray with it, so that is quite a substantial amount in there. She has it under the the grill, yeah, right? So then she takes out the potatoes, she drains them, she keeps, puts them back into the pot and she shakes the pot with the top on so they fluff up. They get like a sort of a crankiness on the outside of them, but it’s fluffy. Right? And then she takes those potatoes and places them into the boiling oil. Boiling oil, smoking, hot oil, smoking hot, so that the kitchen is filled with smoke. She does that and then puts them back under in the oven. And the place is filled with smoke, we’re panicked, you know, we think I go, What are you doing? She goes, I’m making roast potatoes, that’s the way we make them. And then they come out and they are the most incredible thing in the world, because the outside is all crispy, crunchy and the inside, so the outside is like a French fry. Yeah. And the inside is like a mashed potato.

Kate: That does sound-

Stanley: And that’s a classic English dish that you served with the Sunday roast.

Kate : Nice.

Stanley: Amazing.

Kate: You know, this beautiful thing you said, if you don’t mind me saying you, but in a less resonant voice, you said food at once grounded me and took me to other places. It comforted me and challenged me. It was part of the fabric that made up my creative self and my domestic self. It allowed me to express my love for the people I love and make connections with new people. I might come to love. When I see you, I see a man deeply in love with the world and with its deliciousness, and I am so grateful that you shared that with me today. Thank you so much for doing this.

Stanley: No, Kate, it’s been my pleasure. I can’t thank you enough for all the nice things you said and for giving me the time to talk.

Kate: The trick to losing is to do it all at once. I had a dear friend offer some gentle advice after my initial diagnosis. He told me that for people who hiked the Appalachian Trail, the first trailhead is the most important. Eager beginners start their trek with heavy packs brimming with tarps and tents, cooking utensils and flasks and granola bars. But the hiker is already starting to flag, and they have only just begun. They have reached a moment of decision, the moment to ask what can I set down? This will be a hard journey, my therapist said, looking at me a little sternly, is there anything you could set down? Setting down, as it turns out, is difficult. That is until, of course, I had to rebuild, take things on again, pick things back up. This conversation with Stanley Tucci reminded me that it is OK to delight in life again, to be picky and have favorite flavors, to want dinner made and consumed in the correct order. So here’s a blessing for all of us learning to delight again to pick up our joys again once more. Blessed, are you the pragmatic who have run the math and know what adds up and what doesn’t. You have set it all down. You who don’t hope or dream or plan anymore, because what’s the point? But blessed, are you learning to live here. Your world has shrunk. Pain or grief or fear has sucked up every bit of oxygen from the room and every ounce of delight has been squeezed from your hands. But blessed are we who discover that even in the smallness, our attention might be compressed even more? We who pull out a magnifying glass to discover the notice, to taste, to smell the small joys and simple pleasures that make a life worth living. You who wear the fancy blouse because it makes you feel nice long after you thought your body wasn’t worth decorating. You who eat the over-the-top meal, because that is what today can afford. You, who make the memory and plan the trip to snap a picture because we know that this one wild and precious life might cost us everything. So why not make it not just bearable, but beautiful?

Kate Bowler: Our work on the Everything Happens podcast and with the Everything Happens Initiative is made possible because of our partners and generous donors Lilly Endowment, the Duke Endowment, Duke Divinity School and Faith and Leadership. An online learning resource and a huge thank you to my team who makes this work not only possible, but fun. Jessica Ritchie. Harriet Putman, Keith Weston, Gwen Higginbotham, Katie Mangum, AJ Walton, Katherine Smith, Mary Jo Clancy, JJ Dickinson, and Jeb and Sammi. And if you’d like to be a human with me, come find me online at KateCBowler. I also have a weekly email that might be the right dose of love and courage you need. Sign up, I’m KateBowler.com/newsletter. This is everything happens with me, Kate Bowler.

Leave a Reply