Kate Bowler: Hi, I’m Kate Bowler, and this is Everything Happens. This podcast is about those moments when life just cracks open and how people move forward from there.

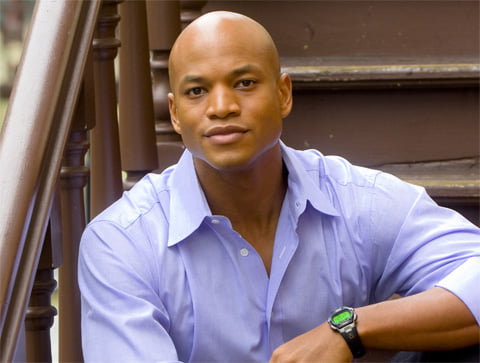

Wes Moore grew up in a tough neighborhood in Baltimore and lost his father at a young age. And there were many moments when his life really could have gone off the rails. But now he’s an incredible justice warrior and storyteller. He’s a bestselling author, a television producer and a decorated army officer. He founded BridgeEdu, which helps students transition from high school to college. And he leads the Robin Hood Foundation, which helps fund schools and food pantries and shelters in New York City. He wrote the bestselling book “The Other Wes Moore,” which we’ll be talking about today.

Now, Wes has a clear position on what it takes to make it in America. Not just hard work, not just luck, but something Americans don’t usually talk about as much … the life-giving help of other people. Wes, I am so lucky that you’re here today.

Wes Moore: It is absolutely my honor, Kate. Thank you so much, and thank you for who you are.

KB: Aww, well I’m sad to be so Canadian so early on, but I will say that as a Canadian, I do find it really striking about the mythology of this country with its obsession about who is deserving and who’s not. Like this sense that life is always fair or with hard work and hustle — or that people should pull themselves up by their own bootstraps. But your book starts on a totally different note. Would you mind reading that first paragraph of your book for us?

WM: Absolutely. “This is the story of two boys living in Baltimore, with similar histories and an identical name: Wes Moore. One of us is free and has experienced things that he never knew to dream about as a kid. The other will spend every day until his death behind bars for an armed robbery that left a police officer and father of five dead.

“The chilling truth is that his story could have been mine. The tragedy is that my story could have been his. Our stories are obviously so specific to our two lives, but I hope they will illuminate the crucial inflection points in every life — the sudden moments of decision where paths diverge and our fates are sealed. It’s unsettling to know how little separates each of us from another life altogether.”

KB: Wow. Well, tell me how and why you decided to start pursuing getting to know that other man named Wes Moore.

WM: You know, it’s interesting because there is this idea, this form of a mythology around the American dream.

KB: Yeah.

WM: Right? And first as if that dream is not one that Canadians or Brazilians or Ghanaians or anyone else hold. But it’s this dream of mobility.

KB: Yeah.

WM: Right? It’s this dream that you can sacrifice now and it will benefit you or at least benefit your children or future generations, some of whom you might not ever even meet. But there is this idea that tomorrow will be better than today. Right?

KB: Yeah, yeah.

WM: And I remember at around the same time that I was receiving a Rhodes scholarship, and I was getting ready to go to England — and, you know, I was one of 32 Americans and one of 90 students around the world who received this scholarship.

KB: Wow.

WM: There was oftentimes this celebration, where you’re on the front page of the local paper and people talking about how wonderful this is. And in this same newspaper, they have a whole series of articles about this robbery that left a police officer dead. And the thing that was really striking was, at the same time while the world was largely celebrating where I was and what I was doing, there was a larger castigation of Wes. And the real in-depth analysis about how either one of us got to where we got was absent. It was just simply a celebration and a castigation, which was really striking.

And I found myself when I was then overseas having all these questions that I knew I wanted answers to, and I was curious about, and I knew Wes was the only one that could answer them. So one day, I just decided to write him a note. And literally the first note that I wrote him was a letter and me saying like, “Hey Wes, you know my name is Wes. Here’s how I heard about you.”

KB: Yeah.

WM: And all these questions. And then he wrote this letter back to me, and, you know, he didn’t have to write back.

KB: Yeah.

WM: But I received a letter back from him a month later from Jessup Correctional Institution. And that letter was insightful and thoughtful and interesting, and it showed how interested he was. And it only led to more questions, and then that one letter turned to dozens of letters. Those dozens of letters turned into dozens of visits. And that really became the premise and the base for wanting to tell this story.

KB: And it struck me, too, the kind of generosity with which you met each other, like you’re both looking for answers there.

WM: Yeah.

KB: And for the person who hasn’t read the book, can you tell me some of the things that you discovered that make you seem to have these parallel lives?

WM: Yeah. And this goes to the power of individual decisions. I remember once a student asked me, “Are certain decisions more important than others?”

And I told him I thought it was a really interesting question, and the honest answer is yes. I mean, certain decisions are more important than others. The problem is, we don’t know which ones are which.

KB: Yes, that’s exactly right. I thought of this the other day. Every day is filled with possibilities and inevitabilities, with only the slenderest separation between them. How do you figure that out?

WM: That’s right, and that’s so beautifully put. And it’s absolutely right. Yhere are decisions that we’re making every day. I mean, both you and I, Kate, before the end of today, we’re going to make 25 decisions that are going to help to determine what tomorrow is going to look like.

KB: Yeah, that’s right.

WM: Right? And that’s an everyday human reality. Right?

KB: Yeah.

WM: And so when we’re making these decisions – sometimes we make decisions that we think are massive, sometimes make decisions that we think are really small, but we really don’t have an idea about consequences of the decisions before and until well after some time the decisions are made.

And so my decision to write Wes, I did not think that … first of all I didn’t even know he was going to write back, but I definitely didn’t think that this was something that was going to change the destiny of my life, or something is going to completely alter the way I think about my existence. But it did. And I’m sure when Wes decided to write me back, I’m sure Wes didn’t look at it and say, “Oh man, I better take this nutter seriously because this could really change everything for me.”

KB: Yeah.

WM: I think he just decided to write a letter to someone who wrote him in prison. And next thing you know, this now became a bond and a connection that has many ways kind of changed the course of both of our lives. So, I think when I first reached out to him the idea of saying, “Okay, here’s a guy who comes from the same city, same neighborhood, we both grew up in single parent households.” We both had academic and disciplinary troubles. We both had handcuffs on our wrists at a very young age.

But here I am – at that time – here I am in England, studying. And here he is – at that time – now at the start of what is a life sentence for him. How exactly does that happen, and how do we get there? And that it was about much more than just a shared name. I think that’s what motivated it initially.

KB: Yeah.

WM: But I don’t think that either one of us knew that this small, what we thought was a small decision, either to write him or for him to write back, would have turned into what it’s turned into.

KB: Well, I love the way your book alternates between your two lives. And you both begin in this really, really terrible place. Your dad had this awful experience at the hospital that struck me so much, because I when I was really, really sick and very openly dying, I went to the E.R., and they sent me home with Pepto Bismol. And I went back again and again, begging for a diagnosis. So I eventually got some kind of treatment. But your dad didn’t get that second chance. Can you tell me a bit about what happened?

WM: So he was a radio journalist, the breadwinner of our family. And he was complaining because he felt like something was going on with his throat. And he actually finished what turned out to be his final show one evening, and that night, he was trying to get to sleep and he couldn’t sleep because his throat was bothering him too much to the point that he was trying to actually take medication, take Tylenol or something along those lines. And it wasn’t going down his throat. He then goes to the hospital the next morning. He actually took himself because my mom was going to take us to school, or to daycare.

And when he showed up, he was tired because he hadn’t slept. He was – he looked disheveled, and there was an assumption that he did not have insurance. And he was trying to explain. But obviously wasn’t heard.

KB: Yeah.

WM: And so he was sent home with the simple instructions to get some rest. And if it gets worse, to let them know. And went home, and five hours after he got home, he died. And literally died right in front of us. He was suffering from something called acute epiglottitis.

Our epiglottis is a little flap of skin and every time that we speak, or every time that we chew, or every time we breathe, it lifts up, and it’s allowing air into your body. And essentially what acute epiglottitis is, it’s where the epiglottis gets so swollen that it sits on top of the windpipe and is unable to lift itself. So basically his body was suffocating itself.

And when the medical personnel came, my mother – you know, he collapsed right in front of us – my mother then called 911. When they came, at that time they didn’t have the medical understanding of, and there’s actually a technology and a tool now that actually can lift – stick something in the throat – and lift up the epiglottis to give air. But that wasn’t around then, and he passed.

And so at that time, instantaneously and unexpectedly, my mother became a widow. And she was now going to raise these three kids in a really complex neighborhood on her own. And I think that very quickly became too overwhelming for her.

KB: Well, your mom’s reaction, in her search for agency– I mean, it was so striking to me how she’s struggling with “What ifs,” and she’s second guessing herself about what she might have done differently. And then she even establishes this fund to train paramedics on the techniques that might have saved your dad’s life. What a search for like traction in a situation in which there should have been a different way.

WM: Yeah, and I love the way you phrase that. Because I think that’s what she was fundamentally looking for, was a sense of grounding when everything else feels like it’s sinking around you. Right?

KB: Yeah.

WM: Her focus at that time became, “I just want to make sure that no one ever has to feel this way that I feel, especially for something that’s preventable. Especially for something that doesn’t have to be, that shouldn’t have to be the case.” I also think that that was one of my mother’s core ways of dealing with that pain and dealing with the fact that she, now, was going to be living a life forever and that this was not a life that she had prepared for.

KB: Yeah, or chosen. Yeah, that’s right.

WM: Yeah. Or chosen.

KB: That’s the feeling: “I didn’t choose this.” With my own diagnosis, I did find that moment totally changed my view of how much we control our lives.

WM: Yes, yes. And it strengthens that fundamental empathy.

KB: Yes. Wow.

WM: Because we’re all we’re all dealing with things. And the truth is that we don’t know what someone else is dealing with when they’re dealing with it because oftentimes people just put on a brave face.

There’s a great poem by Paul Lawrence Dunbar called “We Wear the Mask.” And he says, “We wear the mask that grins and lies, and it hides our teeth, and it shades our eyes. This debt we pay for human guile, with bleeding and broken hearts, we smile.”

And you realize how many people are walking around wearing the mask every single day.

They’re taking on pain, and they’re internalizing a pain that they are then dealing with on their own.

And so our job, our exclusive goal, should be to do what we can do to ease the pain that someone else might be feeling. And it comes back to the idea of, do we want to live with a sympathetic love, or do we want to live with an empathetic love?

KB: Mm, yeah, tell the difference. I like this already.

WM: Well, I think … because a sympathetic love is a love where you’re basically saying, “Well I’m doing this because I feel bad for you.”

An empathetic love is, “I do this because your pain is also mine.”

KB: Well that’s honestly like … that struck me over and over again in your book. Your family gets cracked open in a way that everyone is desperate to avoid. No one wants the moment where there’s the “before” and the “after,” and “before” is so much better.

WM: Yeah.

KB: And then after, though… And your distinction between sympathy and empathy. You let yourself then be cracked open to the pain of others in a way that pushes out instead of folds itself back. You’ve really chosen … do you think that it’s a choice? I kind of think it’s a choice.

WM: You know, I do think it’s a choice. But I think it’s something that if all of us just take a moment to appreciate and understand our own circumstances, I think people will realize that this is not a choice, that this is a fundamental moral and societal obligation.

KB: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

WM: But you know what was really interesting and actually really informative was, this was a real growth experience even telling the stories of these two boys for me. I wanted to write this story so we can really take the reader on a journey.

Where you can look at the back flap and get: oh yeah, two guys, same name, one’s in jail, one’s not. Got it, right? But let’s start the book at its most elementary point. Let’s start the book with the kid who’s four, who watches his father die in front of him. And let’s start with another kid who’s six, who meets his father for the first time. And start there, and then let’s go on a journey about the decisions that these boys were making, the policies that were in place, that were impacting their lives, the people who they had in their lives who are helping them to make those decisions, and the context in which all those decisions were being made.

And then let’s help people to understand that that initial conclusion that we all might have gotten too quickly, which in fairness is oftentimes glib and incomplete is actually much more complex than people think. Because one thing I tried to show with the book was, there were specific moments in both of our lives that helped to determine the rest of our lives. And some of those moments were things that we had no control over.

WM: One of the first things we talk about was, Wes’ mother was the first one in her family to go to college. She graduated from Baltimore City Community College with honors and then got accepted at Johns Hopkins University. And then, as she’s a student at Johns Hopkins University – first one in her family go to college – she then receives a letter indicating that her Pell Grants were cut. And Pell Grants is a program that really helps under-resourced and low-income students receive support in order to pay for the cost of higher education.

And so when his mother has her Pell Grants cut for the second time in three years, she now realizes that she cannot afford to finish school, and she never went back. And so she’s now walking around with debt, no degree, and I can’t help but think how different her life could have been had she had a chance to finish college.

Because it’s not just about the piece of paper, right? If she moved up in education, her networks would have changed, her friendships would have changed, her connections would have changed. And now you fast forward 20 years later, when it’s not just Wes, but it’s Wes’ older brother, her oldest child, who is now getting picked up on charges of murder. And you think about how these things have consequences, and how those type of decisions – the decision to cut the Pell Grant program – it did not just impact Mary Moore, it impacted Wes.

Because it now limited the opportunities that, he — a young man who was simply born into this situation — it limited the opportunities that he was going to have for his life. And so when we talk about individual decision-making — and I feel like there’s a real core and distinct marriage between the two, that it’s both personal responsibility and a societal responsibility. But oftentimes we talk about personal responsibility as if that becomes the end all, be all thing that can increase mobility. And frankly, it’s not. There is a marriage of the two, and both have to be understood when we think about where people are.

KB: Like you had a moment where my life got really shiny. So you become a Rhodes scholar. I’m finding a ladder, and I’m just climbing it. And all of a sudden I have a job, and it’s just one of the best jobs in the field.

WM: Yeah.

KB: And I’m experiencing that trajectory of unlimited possibility. And then the second I get sick, everyone rushes in with an explanation of why tragedy lands on me. So, maybe I’m sick because I ate the wrong things, or maybe I had the wrong habits, or maybe I didn’t pick the right health care provider.

But from the first moment that you reject these simplistic reasons why some people’s lives end in tragedy and others in triumph….How do you convince people who want to believe that you never, ever could have turned out to be the other Wes Moore?

WM: You know, people, after they’ve read this story, will oftentimes come up to me and say “I would have never have known.” Looking at you now, Kate, people would have never known how sick you were. You know what I mean?

KB: Yeah.

WM: And that’s saying something beautiful about your journey and your triumph, right? The fact that you stand here not just powerful, but empowered, right?

KB: Aww, thanks.

WM: And empowering to other people because you are now — you went through the fire, and you came out from that fire stronger.

KB: Oh Wes, you are a preacher. Come on down to the Divinity School! I love you, that’s awesome.

WM: No, but I think that there’s something beautiful about that. But, I think what it also means is, people must be vulnerable enough to be able to understand your journey.

KB: Yeah, like “take off the mask.” I loved that poem.

WM: Yes.

KB: But the heartache underneath is that sometimes things just come undone. And the rest is… the rest is beautiful, too. But so much of it hides the reality that at some point it might actually not have worked out.

WM: Yes. Yes. I’m glad that I went through what I had to go through because I feel like it gave you a sense of armor. And I just feel like there’s nothing that I will ever, ever see again, because of my life experiences both growing up, my time in the military … There is nothing I will ever see in my life that is ever going to make me flinch. And I just feel like my life prepared me for that, right? Where I have an armor that is pretty thick now.

And it’s because of the preparation. Every experience was just throwing another piece of medal on you, throwing another piece of medal on you. And now you’re walking around like Iron Man and Iron Woman. You know what I mean? Like, you’re prepared for battle because of the experience you’ve had. Now, when you’re going through it, it doesn’t feel that way.

KB: It just feels like you’re inside out.

WM: Yes! When you’re going through it, there is nothing more painful, nothing more hurtful when you feel like this is my reality and it’s not going to change. Right? You know, when I think about the fact that there were so many reasons and so many things that my mom could have easily just given up. Just said she couldn’t do it.

Every single moment where life — as soon as she felt like she was getting her head above water — where life just goes ahead and pushes her head down again. You know, she, in addition to raising her kids, she was also dealing with the fact that she had to move back in with her parents. She was helping to take care of her parents while also taking care of her children. And, by the way, she didn’t get her first full-time job with benefits until I was 14 years old.

KB: Oh my gosh.

WM: So she’s working three different jobs, literally waking up at the crack of dawn, going to her first job, wasn’t even taking us to school because she was already out the door. By the time she got in from her last job, we were already asleep.

This was her reality, and it was all that she knew how to do. She got her first full-time job with benefits when I was 14 years old, the first job she ever got that gave her that gave her retirement, that gave her health care, that gave her reliable hours. And she never stopped fighting.

But what she did was, she found the thing to fight for, and for her, it was her kids. And I learned it from my mom, the idea that if you never forget what you’re fighting for, you’ll never stop fighting. And that’s something I think we all have to embrace. Find that thing that you’re fighting for, and you will never stop fighting.

KB: It’s like the quote, and I’m embarrassed to say it’s a quote I keep in my bathroom, because then I can do my hair and read it. But it says something like, “You never know how strong you are until you know how strong love has made you.”

And I do find that feeling of being broken open connects so deeply to a sense of agency. When I look at my son and wanting to be the person … I was always so afraid of being the thing that happens tohim. Because when you’re sick, you are the bomb that goes off, you are the tragedy.

And then wanting to be the kind of person that shows him instead that, in the midst of pain, there is beauty and truth there. And if I can then show him the way through, then I’m the kind of person who’s put on him that kind of armor you are describing.

Because that’s just it, right? It’s like, you can’t promise anyone you work with that their life is not actually going to get harder in so many ways.

WM: You’re absolutely right. You know, Robin Hood has been around for 30 years and works with millions of New Yorkers and people who are around the country who find themselves in this horrific and this incredibly nasty cycle of poverty that we have within our society. And you’re right, you can’t guarantee that you can fix things overnight. I mean, nobody can.

WM: But you can guarantee to everybody, who that happens to be their current reality, you can guarantee that they’re not fighting it alone. That we all collectively are bringing this empathetic love to this fight. We’re bringing an impatience to this fight.

And honestly, there’s a real personal sense of motivation behind it because of the fact that I know I stand here because there were people who believed in me before I was ready to believe in myself. Right?

I stand here because there are people who believed that this child, this son of an immigrant deserved an opportunity to experience an American promise just as any other child.

KB: Yeah.

WM: And that there was never going to be any accident of my birth — not being black, not being poor, not being from Baltimore, not being from the Bronx, not being fatherless — that was ever going to define me or that was ever going to limit me. And I think that’s the way we have to approach our work. Our work isn’t simply about how do you address food, or how do you address housing, or how do you address transportation, or how to address whatever. It’s how do you lift up freedom? Freedom.

Basic freedom and a basic belief that your life is yours, and your destiny is yours and should not be controlled by a circumstance or a structural limitation that was put in place oftentimes before you were even born. There is something so fundamentally not just un-American, but there’s something so fundamentally inhumane about that.

KB: Oh man. When you describe stuff like this, I feel like, yes, this is a prosperity gospel I can believe in.

Because it’s not the sort that says … that puts the burden on the sufferer. It’s the kind that places the obligation on the shoulders of everyone.

WM: That’s right.

KB: And can you tell me that one moment then where you figured out that life-giving community is the only way forward? When did you figure that out?

WM: You know the first time that I think I actually had it really explained to me, and I’m going to be very honest, I think at this moment I did not really fully understand it. I think it took a little while for me to get it. But it happened when I was about 13 years old. And I really didn’t understand at that time. But I was sent away to a military school when I was 13. And that’s because of some issues that I was getting into back at home, and so I had a mandatory year of military school. And in the first four days, I’d run away five times.

KB: Wow.

WM: And they had these big black gates that surround the school, and they always told us, “If you don’t like it here, there’s a train station going anytime you want.” And so I would just take them up on their offer, and they kept finding me.

And the second to last time I tried to run away, they found me in the middle of the woods because they had drawn me a map of how to get to the train station. And they drew me a map because they said it was so pathetic that I kept on getting lost. But the map was fake. The map took me to the middle of the woods. They just enjoyed watching me do circles in the woods.

KB: Stop it.

WM: So that’s all true. So they brought me back to campus. And we’re in the middle of something called plea system. So there’s no outside communication, no radio, phone, television, nothing. You’re either going to succeed as a team, or you will fail as a team. And the choice was completely yours.

But they said if we don’t make an exception, we’re going to lose him. So they said, “Moore, you’ve got five minutes to make a phone call. Call whoever you want.” And I decided to call the only number that I knew, which was my mom. And I’m calling her, I’m complaining, and I’m like, “Mommy, this is crazy. Listen, thank you for this wonderful opportunity, but I’m really ready to go home.” And all that kind of stuff.

And then she stopped me, and she said, “Too many people have sacrificed for you to be there, and too many people are rooting for you, and you have to understand it is not all about you.” And that was the first time — and again I have to admit, I went to bed that night as angry as I went to bed the night before. I was so upset — but that was the first time I’ve really ever heard it explained to me in that way, that we really do live in a completely interconnected society.

KB: Yeah, you are not your own.

WM: You are not your own. You’re a piece of something big and beautiful and bright, if you so choose.

And this beautiful experiment that’s going on right now, your voice and your presence in it, it does matter. You have to have a level of humility.

KB: Yeah, that’s right. That’s right.

WM: But that humility must be empowered humility. And it’s how I think we have to approach our collective existence.

KB: Man, because that’s the thing that hit me like a sledgehammer. After everything came apart, it was the “you are not special” – only insofar as, I don’t get to be the exception to the rule, that that pain can visit us all. But it was simultaneously an experience in which I have felt more loved in my whole life because everyone just gathered around to fill in all the cracks.

And I wouldn’t have known that if I hadn’t come to the end of myself.

WM: Yes. Yes. And the perspective that that gives you afterwards where, where you were in gentle and protective hands the entire time. And you made it out of a very dark place. You made it. And now you stand in in a glorious light.

So there’s something really beautiful about that. And I think there’s also something that I know — there’s a certain survivor’s guilt that comes along.

KB: Yeah, yeah. Do you have that? Was that a dynamic that you experienced when you were interacting with other Wes?

WM: Absolutely. Every day.

KB: Yeah.

WM: Especially when you know that so many of the factors that led you through were things that you did not control.

KB: Yeah. Like, I don’t have a cancer lab. And really, I apparently don’t set the policies for health care. And I fought so hard to get this one drug. And just that part slays me, because I remember sitting in the bloodwork room in Atlanta, and I’d have to fly there every week. And of course just flying there was an exercise in everybody donating airline points.

And I remember sitting in the blood work room, which was the worst part of the day, and people are coughing blood into their sleeve, and everyone is slumped over and exhausted. And I’m feeling pretty low. And I look outside the window, and there is this older man hunched on the seat waiting for the bus. And I can tell he’s written very poorly the instructions that the doctor gave him on a scrap of paper.

And I thought, “I’m the one that’s has the stage four diagnosis. But I’m pretty sure that guy’s not going to make it.” Having to constantly see the inequality. I’m so grateful, and yet I am no longer my own.

WM: Yes.

KB: Wes, you have given me new language today. I am so grateful you took the time to talk with me.

WM: It’s absolutely my joy. Thank you so much for who you are and what you do.

KB: Isn’t Wes amazing? I love what his mom said. She said, “Too many people have invested in you. This is not about you.” I think it’s so important to remember that as an immigrant from Jamaica, a mom like that knew what it was like to uproot, to invest, and to believe in dreams that cost her greatly. And that kind of love changed his life. The community that surrounded him, that said, “We owe each other to make better choices, to find a different path, or to stay on course.”

Because we just never know what our decisions are going to mean. I mean, I once chose a college based on the fact that the brochure showed people playing rugby. I didn’t play rugby. And I ended up finding one of the only schools that paid good money for international students. We just don’t know where our lives are going to take us. And I hope that randomness gives us, like Wes, a greater charity toward others.

I think of all the people that respond to my situation with minimizing, like, “At least it’s not …” or teaching, “Have you tried?” or solvers, who are just ready to force essential oils, I suspect, on me at any moment. But, I think on top of those categories, Wes Moore would add rationalizers. People want a reason why it couldn’t be them that bad things happen to. We need people like Wes to remind us that we are all the same. This is not about you, he would say. This is about us.

Okay, I can’t believe I get to say this, but I have a special guest coming up. Seven-time Emmy award winner Alan Alda will be on the show, talking to me about how lessons drawn from acting will help us all be more empathetic. Talking to super-famous actors is a totally normal thing for me, so you will notice my behavior is totally normal, calm, cool. I hope you’ll tune in.

And look, if there’s someone you think would make a great guest, I’d love to hear about it. Email me your suggestions at everythinghappenspodcast@duke.edu.

Everything Happens is produced by Duke University, in association with North Carolina Public Radio WUNC. Support comes from Faith and Leadership, an online reading resource.

And so many thanks go to my awesome team, Beverly Abel, Alison Jones, Amanda Hite and the Be the Change Revolutions Team, Ivan Panarusky and Random House. If you’re enjoying these conversations, please go to Apple Podcasts and post a review. And come find me on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @katecbowler.

This is Everything Happens, with me, Kate Bowler.

Leave a Reply