Hosanna! Save us!

When the multitude of disciples welcomed Jesus into Jerusalem 2,000 years ago, they shouted, “Hosanna!”

Hosanna — a word meaning “Save us.”

In desperation for freedom from the oppression of their time, the people called out to Jesus, “Save us!” and were confident in his ability to do so.

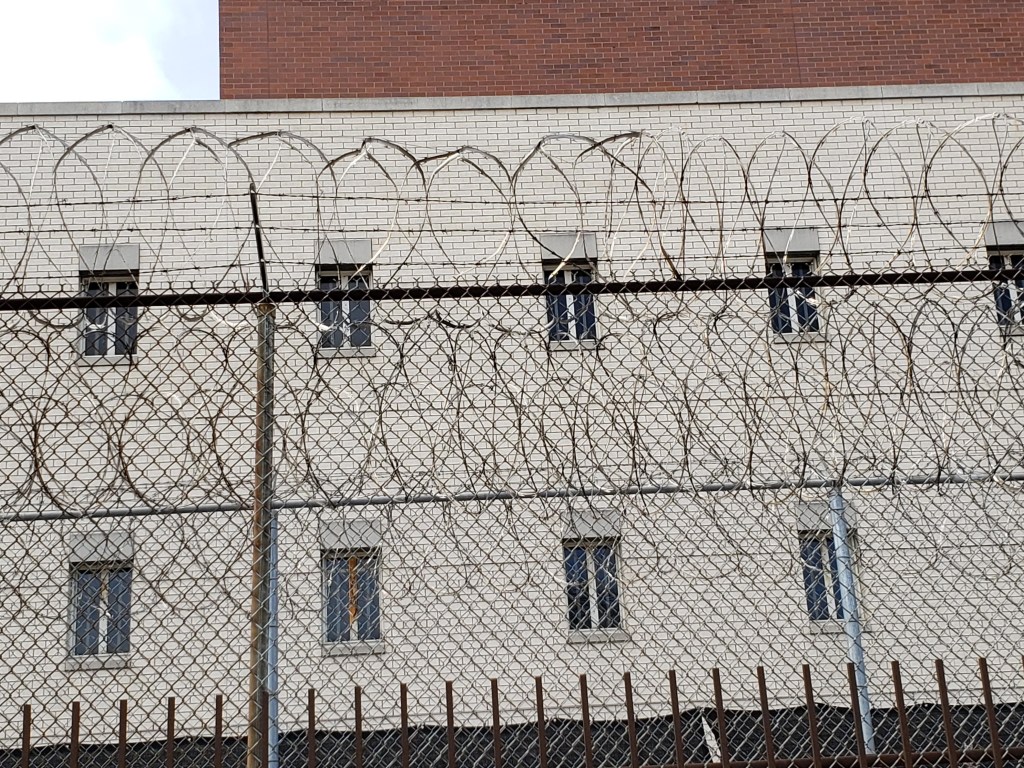

This Palm Sunday, for the second consecutive year, I will join a procession of palm-bearing adults and children as we pray, sing and play instruments around Cook County Jail in Chicago, the largest single-site jail in the country. Some 5,500 people charged with crimes ranging from petty theft to first-degree murder may catch the faint sounds of our voices from their cells inside the walls.

We, too, will shout, “Hosanna! Save us!” Our pleas will mix desperate yearnings for peace, liberation and justice with jubilant confidence in the power of life over death.

Palm Sunday can be a confusing day liturgically. It is triumphant, but foreboding. At Mass, we jump from our joyous waving of palm branches into perhaps one of the most depressing lines of Scripture — “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” — and then into the Passion narrative itself.

I grew up in a parish where, during the Passion reading, the people in the pews represented the crowds shouting at Pontius Pilate to crucify Jesus. As a child, I saw the adults around me following the script and reading their lines without giving it a second thought. I followed suit.

But like standing in the shadow of a barbed wire-topped cement wall, Palm Sunday is an uncomfortable place when we are present to what it represents on the road towards justice.

During the prayer walk, we don’t venture into Good Friday territory quite yet, choosing to dwell in the paradox of the joyful, desperate pleas of the “Hosanna” procession. Yet in some ways, “Hosanna!” is incomplete without “Crucify Him!”

To bystanders, shouting a prayer of “Hosanna, save us” while walking around the jail could mean a number of things. Save us from crime. Save us from violence. Save us from the evil people inside these walls.

But this line of thinking could not be further from the Gospel message of mercy and salvation.

When I hear my own voice not only shouting “Hosanna” but also “Crucify him!”, I realize that my prayer for salvation is not on behalf of poor souls somewhere else, like in the jail. Rather my prayer for salvation is on behalf of all of us, a collective that has strayed so far from God’s vision of right relationship and harmony among all of creation.

Ignacio Ellacuría, who was martyred in El Salvador, urged the Church to see Jesus crucified in the oppressed people of today:

“This crucified people are the historical continuation of the servant of Yahweh, whom the sin of the world continues to deprive of any human features, which the powers of this world continue stripping of everything, wrestling his life from him as long as he lives.”

Certainly, the face of Jesus crucified is reflected in the men and women detained in Cook County jail, and I play a role in their oppression.

I profess belief in a God who extends mercy to all … in a God who brings light to darkness, peace to violence, healing to woundedness and life to death, especially when we join together in community.

Saint John Paul II, building on the wisdom of theologians like Ellacuría, who also prophetically denounced “structures of sin” around them, calls all of us to task in recognizing our own culpability for sinful structures like the carcel system:

“It is a case of the very personal sins of those who cause or support evil or who exploit it; of those who are in a position to avoid, eliminate or at least limit certain social evils but who fail to do so out of laziness, fear or the conspiracy of silence, through secret complicity or indifference; of those who take refuge in the supposed impossibility of changing the world, and also of those who sidestep the effort and sacrifice required, producing specious reasons of a higher order. The real responsibility, then, lies with individuals.”

My very personal sins might range from negligence towards the enactment of just laws to failure to practice mercy in the smallest of interpersonal conflicts in my day-to-day life. Truly, when I refuse to listen to the ways that I have hurt others, when I hold an office grudge, when I belittle my child through yelling or shaming, I contribute to a culture that views justice as punishment and revenge, that sees reconciliation as an unattainable utopia.

Whether facing the structural sins of the carceral system or one of the numerous other intersecting systems that undermine human dignity, I admit to moments of falling into laziness, fear, indifference and even doubting that change is possible.

The point of recognizing the magnitude of structural and personal sin is not to wallow in guilt or despair. This is where I find comfort in the triumphant, desperate plea of “Hosanna, Save us!”. I profess belief in a God who extends mercy to all — to me, to you, to my brothers and sisters in jail — in a God who brings light to darkness, peace to violence, healing to woundedness and life to death, especially when we join together in community.

In this belief, there is joy.